“I used to be pretty suicidal last summer and I tried to commit suicide about two times.”

Since 2018, more than 36,000 students across the Seattle region have shared their hopes, fears and family secrets in an online questionnaire called Check Yourself.

“My dog has … untreatable cancer and my great grandma died a week ago.”

“Some time i harm my self by not eating cause i don’t really like my body.”

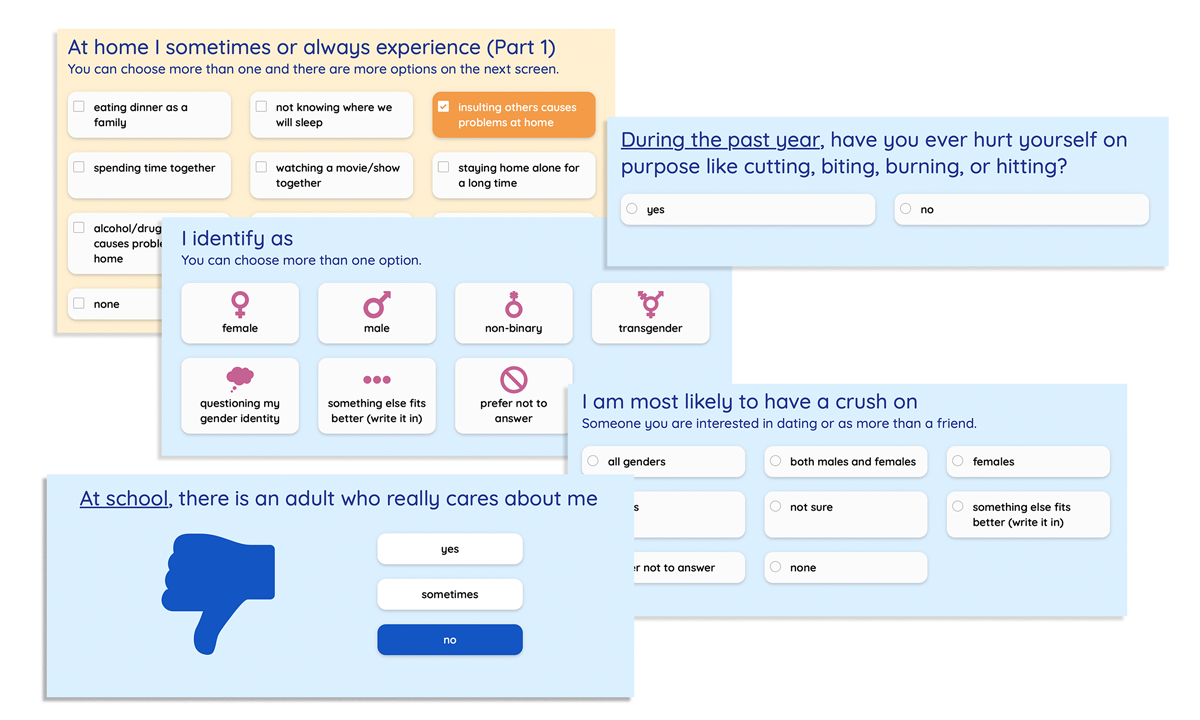

Questions peer into students’ sexual preferences and romantic lives — even which gender they’re “most likely to have a crush on.” It’s the kind of information a 12-year-old might not tell their best friend.

“Do my parents see this survey?”

Districts promise students their answers to over 50 personal questions will be kept confidential. But a group of parents has been able to obtain reams of sensitive survey data from multiple districts through the state’s Public Records Act.

One of them, Stephanie Hager, is on a six-year crusade to expose what she considers to be the program’s lack of privacy safeguards. To prove her point, the former Microsoft program manager said she correctly identified six students based on nothing more than details they provided in the survey and a simple Google or social media search.

“We know their school, gender, age on a certain date, grade level, language they speak, their dogs’ names, friends’ names, race, their unique interests, what sports they play, if they are religious, and anything else they feel like writing in — plus their whole mental health record,” said the Snoqualmie Valley mother of four, whose son took the survey in 2019.

“I can’t imagine any parent saying OK to that.”

Researchers at Seattle Children’s Hospital and the University of Washington developed the Check Yourself program to better identify students in middle and high school silently suffering from depression, substance abuse or suicidal thoughts.

I can’t imagine any parent saying OK to that.

Stephanie Hager, parent, on districts sharing students’ personal data.

Supported by a voter-approved tax levy, King County, which encompasses Seattle, has spent more than $21 million on the program since 2018. The funds help pay for mental health counseling for students and to track trends across the 13 districts that participate. Seven schools in Spokane County, in eastern Washington, and a few districts in Oregon also use Check Yourself.

Backers of the survey have a simple defense: It saves lives.

Valerie Allen, director of social services and mental health in the Highline district, told The 74 of a student who jumped into a pond at a city park in 2022 carrying a backpack laden with weights. The boy went missing after an argument with his dad. The family, Allen said, turned to a school counselor who had started meeting with the student after Check Yourself responses showed he was suicidal. The counselor tipped off police to the pond, the kid’s favorite spot, where they arrived just in time to save him.

The question of whether results like this justify the potential pitfalls have mired the program in controversy since its inception.

“The ultimate protection” against privacy risks is not to do the survey, said Evan Elkin, who helped adapt it for schools and serves as executive director of Reclaiming Futures, a project at Portland State University. But, he asks, is ending the program “worth the lives that you lose?” Officials said they could not determine the number of suicides prevented due to the survey.

(Is suspending the program) worth the lives that you lose?

Evan Elkin, director of Reclaiming Futures

For Hapsa Ali, a 2023 Highline district graduate, Check Yourself came at the right time. She suffered from “really bad social anxiety” and wasn’t getting along with her mom. Based on her answers, the school connected her to a counselor who regularly checked in on her, texting once a week.

“She was my safe space,” Ali said.

The clash over Check Yourself falls at the intersection of social forces that have only intensified since the pandemic. Many teens are experiencing extreme emotional and psychological stress. While recent reports show some improvement since 2021, 30% of 10th graders still say they have persistent feelings of depression and 15% reported thoughts of suicide, according to Washington state data.

Schools are really under a huge amount of pressure to address student mental health.

Isabelle Barbour, mental health consultant

At the same time, school districts house massive amounts of sensitive personal data and rely heavily on ed tech, making them prime targets for hackers. The Highline district, for example, closed for three days in September because of a cyberattack. Nationally, ransomware incidents in education more than doubled in 2023. Online mental health surveys also face backlash from activists and lawmakers, who find them frequently intrusive, inappropriate and removed from school’s main purpose.

“Schools are really under a huge amount of pressure to address student mental health,” said Isabelle Barbour, a consultant who developed a school-based mental health program for the state of Oregon. “But when they try to adopt something that can work in their setting, it brings up all of these other pressure points around privacy.”

‘I shouldn’t be seeing this’

The survey, which takes about 12 minutes to complete, leads students through a series of prompts, from simple tasks such as listing their top goals for the year to deeply personal queries like, “During the past year, did you ever seriously think about ending your life?”

Parents get two chances to opt their children out of the screener, and students can also decline to complete it on the day of the survey. But districts reveal nothing that would alert anyone to its potential risks. Quite the contrary. One district promotes it as a “successful, proactive approach to providing support to students.” Another promises “personalized feedback and strategies for staying healthy.”

In fact, district websites assure parents that only counselors or other “relevant” staff can view individual students’ responses, which are stored on a “secure” platform by Tickit Health, a Canadian company. To participate in the county-led program, districts must sign an agreement saying they will remove all “potentially identifying” student data before submitting records to the county, which uses the information to evaluate the program’s effectiveness and respond to students’ needs. Districts promise that county officials and researchers only see anonymous responses.

But an investigation by county ombudsman Jon Stier, triggered by parents’ concerns, suggests this hasn’t always been the case. A report released last summer revealed that in the program’s early years, county officials were able to connect student names to their responses, although Stier said that practice has ended.

The issue of the survey’s confidentiality first emerged publicly in 2022, when 10 districts released spreadsheets of student answers in response to a public records request from a Seattle Times reporter. Snoqualmie Valley parents asked districts for additional information, released as recently as February 2024, which they shared exclusively with The 74.

A handful of districts concealed some personal details. But several redacted little, if anything.

This could put districts in violation of federal student privacy laws, which require districts to gain parental consent or remove all identifying information from records before releasing them publicly.

Privacy experts say that wiping information such as race, home language and favorite activities from a document in order to make it truly anonymous is no easy task. But without such measures, a combination of answers could identify a student, in the language of the law, “with reasonable certainty.”

Sometimes, just a simple data point can expose a student’s identity.

During the 2021-22 school year, for example, only one student in the Kent district who took the survey identified as being part of the Muckleshoot tribe, which has about 3,000 members statewide.

Most survey questions are multiple choice. But 13 allow students to write open-ended responses — and it is these answers that experts say vastly increase the chances of identifying potential students.

It feels like everybody’s sticking their head in the sand about what the consequences could be.

Amelia Vance, Public Interest Privacy Center

At The 74’s request, Amelia Vance, president of the Public Interest Privacy Center, reviewed an Excel document with answers from more than 900 students in the Auburn district from the 2021-22 school year — details that included random factoids like a preference for techno music and proficiency in math, as well as very private revelations such as conflicts at home and incidents of self-harm.

“I shouldn’t be seeing this spreadsheet,” Vance said. “It feels like everybody’s sticking their head in the sand about what the consequences could be.”

Districts ‘caught off guard’

Marc Seligson, a King County spokesman, insisted that “student data security is paramount,” but that responsibility for interpreting privacy laws falls to the districts.

“We can’t give them legal advice. Each district has their own lawyer,” said Margaret Soukup, the county’s youth, family and prevention manager, who oversees the program.

She said she was shocked districts released records to parents. “I was very upset because I didn’t even think that that was a possibility.”

We can’t give them legal advice. Each district has their own lawyer.

Margaret Soukup, King County

The 74 reached out to the nine King County districts that released records to the public and still use Check Yourself.

Five didn’t respond, and a spokeswoman for Auburn declined to comment. Conor Laffey, a spokesman for the Snoqualmie Valley district, said officials there worked with the county to “safeguard confidential student information” and consulted the district’s legal counsel before releasing spreadsheets. He declined to elaborate.

Tahoma School District Superintendent Ginger Callison, a former Snoqualmie Valley official, said she didn’t remember details about past disclosures and is “confident” that in the future, “nothing will get released that isn’t allowed or required.”

A Seattle spokeswoman noted that records went through “multiple layers of review to remove potentially identifiable comments within student responses.” But the district didn’t redact very specific details about some students, like the one obsessed with reptiles who wanted a pet frog and another who speaks English, Russian, Spanish and sometimes Samoan. The district did not comment on why it included such information in the spreadsheet of students’ answers.

The 74 also contacted Cari McCarty, a University of Washington researcher who helped develop the survey and now evaluates the King County program. She said districts are obligated to protect “the confidentiality of student information,” but directed further questions to the county.

Parents say the county also bears responsibility for students potentially being exposed.

Hager, Check Yourself’s most outspoken parent critic, obtained an email thread through an open records request that shows officials were well aware of the survey’s potential privacy pitfalls. In one email, a former Tickit Health executive warns county officials that if a student “were to enter identifiable information in the free-text sections, theoretically this would be accessible.”

One wrinkle in King County’s privacy dispute is that Washington has one of the strongest open records laws in the nation. In 2016, for example, the state Supreme Court upheld over half a million dollars in fines in a case against a state agency that was slow to turn over records.

Elkin, from Portland State University, said districts were “caught off guard and panicked” when they received the open records requests.

But the Washington districts are no different than many others nationally that currently find themselves fielding more public record requests than ever before — often from watchdogs like Hager or activists investigating curriculum materials they believe to be inappropriate. Spurred on by conservative groups like Parents Defending Education and Moms for Liberty, repeat filers dig for lesson plans, teacher training materials and financial records — particularly those relating to transgender issues and diversity, equity and inclusion.

Allen Miedema, executive director of the Northshore district’s technology department, said the districts that use Check Yourself could “do a better job of letting parents know” about the purpose of the survey.

If staff members failed to conceal student identities, he said, it’s often because they’re “swamped” with requests for documents and lack clear guidance from state or county officials on what’s allowed to be included.

‘Survey gets dark very fast’

School leaders insist the danger is largely hypothetical.

Officials in King County, and from six districts that responded to a request from The 74, said they’ve received no reports of cyberthieves or child predators gaining access to Check Yourself and using results to target students.

They point to internal data showing that students feel more connected to school when they’re referred to an “intervention” after taking the survey. In focus groups, students expressed “favorable opinions” about the screener. In a survey of almost 400 students referred to a staff member after completing Check Yourself, the percentage saying that an adult at school listens, cares and tells them they do a good job increased.

“The tool has been indispensable in pinpointing students who would benefit from urgent extra help — some of whom we never would have known were struggling,” said Laffey, the Snoqualmie Valley district spokesman.

But that doesn’t satisfy Hager.

She is among more than 20 Snoqualmie Valley parents who started asking questions about the program after the FBI warned in 2018 that “malicious use” of sensitive student data could lead to identity theft and “help child predators identify new targets.”

Hager, who attended school in King County, doesn’t have to imagine what it’s like to be preyed on by a trusted adult. In seventh grade, she said she was a victim of sexual misconduct involving a male teacher.

“I know the FBI’s scenarios are real,” she said.

She points to students’ written reflections on the survey as proof that some find the questions disturbing.

“This survey gets dark very fast especially for a child.”

“Why does it act like I’m constantly breaking the law? I’m 12.”

Many students expressed particular concern about questions related to sex and gender. One 12-year-old wrote:

“Female but kinda non binary sorta questioning but not? (Don’t tell my parents).”

Seligson, the King County spokesman, said the survey asks such questions because LGBTQ kids “are one of our most vulnerable populations.” State data released in 2023 showed that LGBTQ youth were nearly twice as likely as other students to report “depressive feelings.”

The unease some students expressed about Check Yourself was echoed by several district staffers.

In 2019, an official in the Tukwila district, south of Seattle, wrote in a report to the county that the survey was “causing considerable angst” and that with many “vulnerable” and “traditionally marginalized” families, educators didn’t want to “create unnecessary harm.”

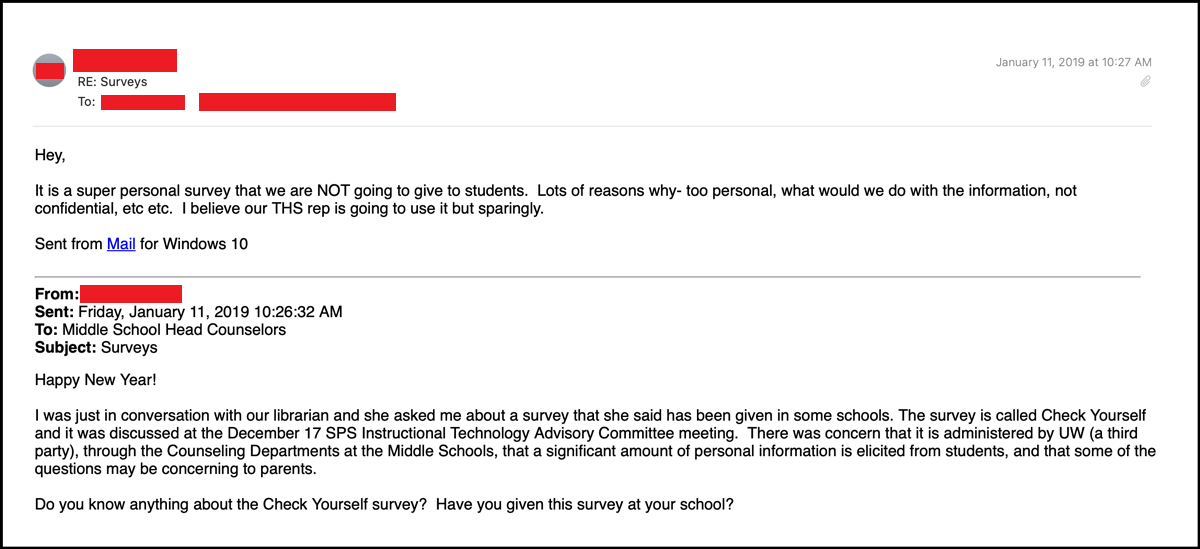

That same year, a Seattle school counselor called it a “super personal survey,” according to an email The 74 obtained through a public records request. She questioned why the district needed the information and whether it would be able to keep it confidential.

‘Absolute data privacy is a fantasy’

To be sure, not all King County parents have a problem with Check Yourself.

Erica Thomson, who works for a cloud communications company, said the notion of “absolute data privacy is a fantasy.”

She has two boys in the Seattle schools, one who is transgender and the other who has ADHD, and appreciates that the program gets her children to open up.

“Kids do not tell parents everything,” Thomson said. “Sometimes it is because they love their parents too much and do not want them to worry or suffer.”

Some students write that they appreciate the survey experience, which includes targeted recommendations based on their answers. A student who reports using marijuana, for example, will get facts about how it negatively affects memory and mental and physical health.

Ali, the former student who found Check Yourself beneficial to her well-being, had a distinctly nuanced take on her experience.

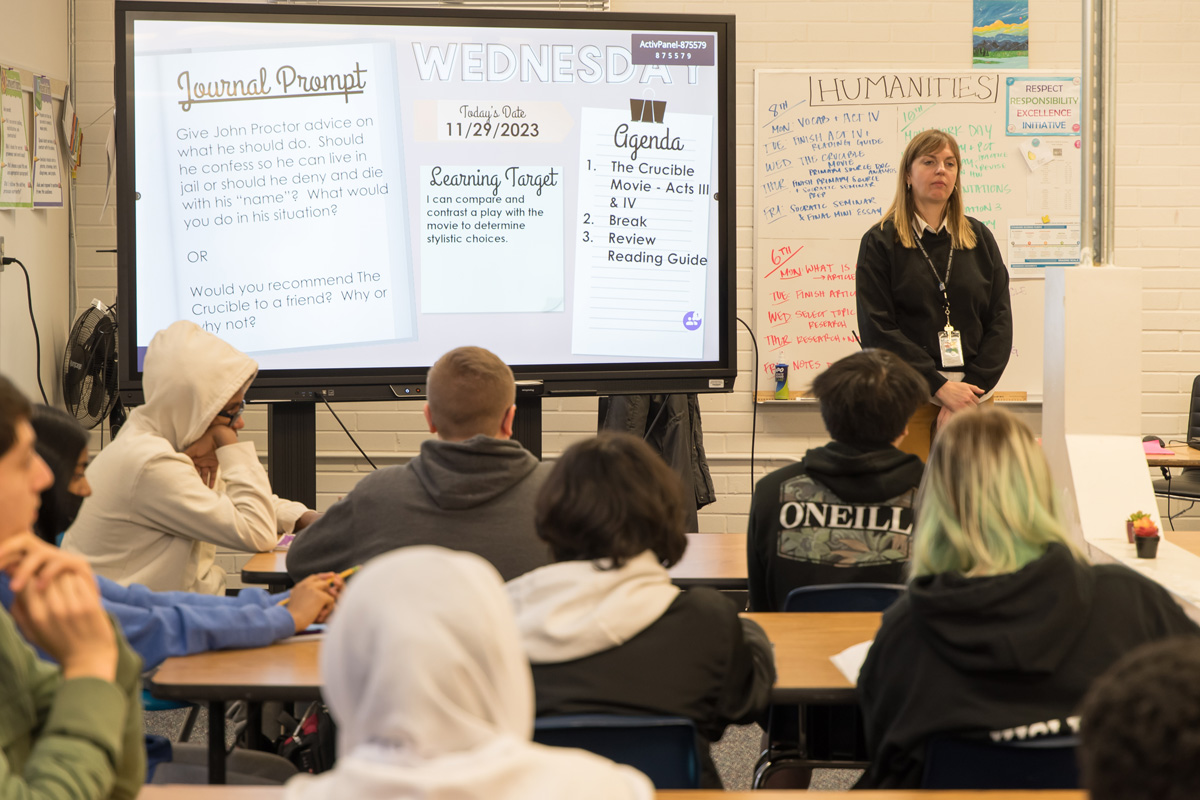

While praising the personal attention she received from a counselor, Ali described a “rowdy” atmosphere in the sixth-period history classroom where she took the survey, with classmates buried in their phones and chatting with friends. It made it difficult to express some of the conflicts she was experiencing at the time.

“It was a bunch of juniors just goofing off. I was sitting next to my friend, and she would just ask me, ‘Oh, what did you answer?’” she said. The atmosphere, she added, “felt like it wasn’t as serious as it should have been.”

The information is ‘too valuable’

As King County parents and school officials debate the merits and risks of Check Yourself, other districts have managed to use the program with relative ease.

In Oregon’s Hillsboro district, students’ responses stay on the Tickit platform — unavailable to outside evaluators or the public at large.

Spokane County officials not only eliminated questions about sexual orientation and romantic attractions, but also removed open-response fields.

“Why is it necessary for us to have that information?” asked Justin Johnson, who leads community services for Spokane. Additionally, clinicians monitor the administration of the survey in classrooms, allowing the results to be covered by stricter medical privacy protections.

But Soukup, the King County official who oversees the program, said districts there find the write-in answers “too valuable” to do without because students often use them to open up about their problems.

For some King County districts, however, Check Yourself simply proved to be too much.

The Lake Washington district pulled out of the program three years ago and instead contracts with full-time mental health specialists to respond to students’ needs.

The intensely personal questions — and the resulting risk of privacy violations — also helped push the Bellevue school system to drop it in 2019.

Officials opted for a different survey, and because of their sensitive nature, results are “considered some of the most privileged data the district has,” said Naomi Calvo, who served as Bellevue’s director of research, evaluation and assessment until 2023. “I didn’t even have access to it.”

Calvo understands why districts jumped to implement Check Yourself and most continue to use it. “Students have needs that were going unaddressed and there is a dearth of options available,” she said.

But as a mental health professional with a young son at the time, she felt skeptical.

“As a researcher, I believe in surveys,” she said. “But I would not have let my child take that survey.”

This story was co-published with The Seattle Times.

If you or someone you know is having thoughts of suicide, call or text 988 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. Additional resources are available at SpeakingOfSuicide.com/resources. For LGBTQ mental health support, you can contact The Trevor Project’s toll-free support line at 866-488-7386.

Free, confidential treatment referral and information is available in English and Spanish at 800-662-4357, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Helpline.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter