It’s hard to count insects.

Even as scientists have found that many populations are in decline, they’ve struggled to understand the scale of what’s happening. Now, a groundbreaking new study offers the most comprehensive answers to date about the status of butterflies in the contiguous United States.

In 20 years, the fleeting time it takes for a human baby to grow into a young adult, the country has lost 22 percent of its butterflies, researchers found.

Check out the butterflies in your area

In New York, N.Y., 128 species included in the study are known to occur.

Here are a few you might see:

“The loss that we’re seeing over such a short time is really alarming,” said Elise Zipkin, a quantitative ecologist at Michigan State University and one of the authors of the study, which was published on Thursday in the journal Science. “Unless we change things, we’re in for trouble.”

Little-understood and vastly underappreciated, insects play an outsize role in supporting life on earth. They pollinate plants. They break down dead matter, nourishing the soil. They feed birds and myriad other creatures in the food web.

“Nature collapses without them,” said David Wagner, an entomologist at the University of Connecticut.

Dr. Wagner, who was not involved with the new research, called it a “much-needed, herculean assessment.” He praised the study’s rigor and noted that the declines in butterflies, amounting to 1.3 percent per year, were in line with other recent efforts to analyze global trends in terrestrial insect populations.

Still, researchers didn’t have enough data to include some of the most imperiled butterfly species, which probably experienced some of the steepest declines. And the data was quite likely biased toward places where butterflies tend to show up. “Unfortunately for nature,” Dr. Wagner said, the findings are “undoubtedly a conservative assessment.”

The analysis was based on 12.6 million individual butterflies counted in almost 77,000 surveys across 35 monitoring programs from 2000 to 2020.

Change in butterfly abundance, 2000-20

Data for the contiguous U.S.

That data came largely from volunteers who, working with various programs, showed up in a certain location on certain days over the years to document every butterfly they saw.

The researchers — some who specialize in math, others who are experts in butterfly species and behavior — took that raw data and harmonized it, creating a model that estimated the changes in abundance.

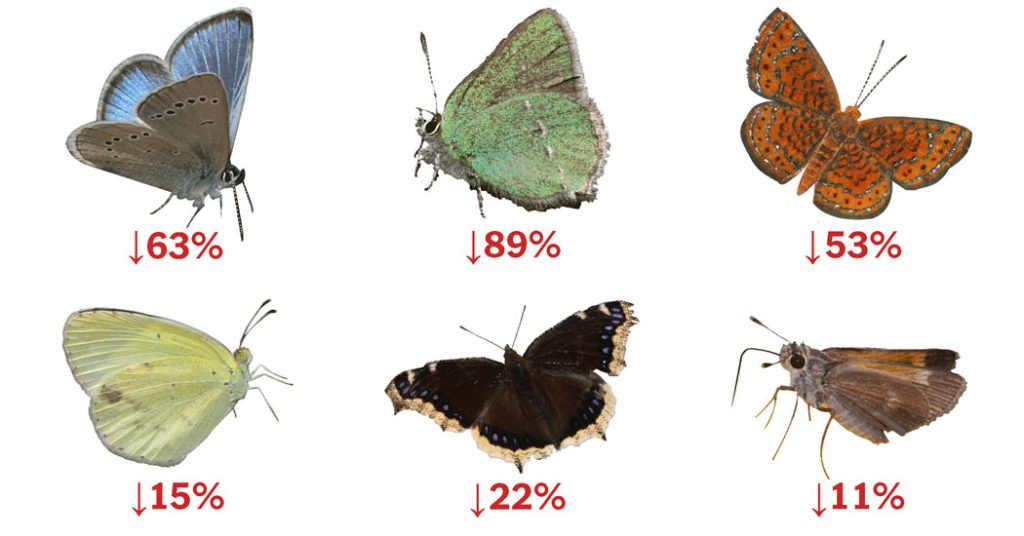

Of the 342 species for which they were able to draw conclusions, 33 percent showed statistically significant declines and less than 3 percent displayed statistically significant increases. Thirteen times as many species decreased as increased.

The American lady, an orange-and-black butterfly that ranges from coast to coast, was down 58 percent.

The Hermes copper, a rare butterfly found in San Diego County, plummeted by 99.9 percent.

Even the cabbage white, originally from Europe and so commonly found munching on vegetables as a caterpillar that it’s considered an invasive pest, dropped by half.

“That shocked me,” said Nick Haddad, an insect ecologist at Michigan State and an author on the study. “If even the cabbage white is declining, then, oh my God.”

The research could not shed much light on how monarch butterflies are doing, the authors said. Monarchs, which the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in December recommended for federal protection, have shown staggering declines in their overwintering sites in Mexico and California. But separate new data offered a dose of good news on that front: After hitting an almost record low last year, overwintering monarchs in Mexico rebounded significantly in this year’s count, made public by the Mexican government and the World Wildlife Fund on Thursday.

Scientists attributed much of the increase to an easing of drought conditions along the migration route of eastern monarchs, which travel between the United States, Canada and Mexico. But monarchs west of the Rocky Mountains, which overwinter in California, were at near record lows in this year’s count.

Why are butterflies crashing? Experts blame a combination of factors: habitat loss as land is converted for agriculture or development, climate change and pesticide use. What’s less clear is the extent to which each factor is driving the declines.

The study doesn’t try to answer that question, but it points to other findings, from the Midwest and California, that insecticides have played a particularly lethal role. A class called neonicotinoids, which Europe largely banned in 2018, was found to be especially deadly.

Members of the public are often called upon to plant native milkweed to help monarch caterpillars, but a study in the Central Valley of California found that every single collected sample was contaminated with pesticides. That was true even when landowners said they did not use pesticides, suggesting that the chemicals had drifted or had been applied to plants before purchase.

The new findings do show potential fingerprints from climate change. As the world warms, North American species are moving northward in search of more hospitable conditions. When researchers compared the same species in neighboring regions, they found that the northern populations were faring better than southern ones in three-quarters of cases. Moreover, two-thirds of the species that showed overall increases in the United States have ranges with more area in Mexico than in the United States and Canada, suggesting that perhaps they are growing in the northern parts of their range. Without data from Mexico, researchers can’t tell what’s happening there.

The researchers emphasized that solutions are at hand. Some, like tackling climate change and regulating pesticides, need to happen at the policy level. But in the meantime, they encouraged people to create habitat refuges for butterflies and other insects by planting native flowers, shrubs and trees. One butterfly, the Gulf fritillary, appears to have increased its range as homeowners planted passionvine, which its caterpillars eat.

And remember those caterpillars, said Collin Edwards, an ecological modeler for the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the lead author of the study.

“If you’re spraying something on your plants to keep things from eating them, caterpillars are eating plants,” he said. “Those are butterflies-to-be.”

Methodology

The data in this article come from Edwards et al. (2025) and were provided by the researchers.

The study groups species into five categories: declining, possibly declining, little change, possibly increasing, and increasing. Species in the declining and increasing categories saw changes of at least plus or minus 10 percent. Those with trends that were not statistically significant were classified as possibly declining or possibly increasing. For the purposes of this article, possibly declining species were grouped with declining species, and possibly increasing ones were included in the increasing category. The researchers’ data and code can be accessed here.

The lookup tool includes 235 species. Their ranges are based on Grames et al. (2024). The list of places is based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s Places and County Subdivisions files.

The species’ common names used in the lookup tool are based on the North American Butterfly Association checklist.