Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

For 20 years, teachers in North Carolina’s Caldwell County Schools relied on one textbook and their imaginations to teach elementary science.

Fourth-grade teacher Megan Lovins would study the county’s curriculum guides each year to piece together the best science lessons possible. But in 2021, bulky, blue crates arrived at her classroom door in Hudson Elementary — and a new way to teach science practically fell in her lap.

Her district had agreed to participate in a multi-year trial to study the impact of new curriculum and professional development on student achievement.

A Newton’s cradle to demonstrate physics. Empty tin cans to help illustrate static electricity. Measuring cups, tape, rulers and more. As Lovins emptied the crates, she realized she had all the equipment needed to teach tangible science activities.

“I am a hands-on teacher, so I fell in love with it instantly,” she said.

The materials were part of a five-year randomized controlled study by the Smithsonian Science Education Center that launched in the 2019-20 school year. With a $4.5 million federal grant, the center provided its own high-quality science curriculum and professional development to 37 schools in North and South Carolina to study how combining the two impacted test scores.

Researchers found that pairing the curriculum, “Smithsonian Science for the Classroom,” with high-quality professional development improved students’ science, math and reading test scores. The study also showed positive results in science for students who are typically underrepresented in STEM fields, such as girls and children of color.

“There’s no other randomized controlled trial study that’s done this in elementary school using these standards,” said Carol O’Donnell, the center’s director. “So this is a big deal for the field.”

The trial followed 1,600 students in third through fifth grades over the course of three academic years. Of the 37 schools, 19 were classified as “treatment” and given the Smithsonian curriculum and professional development, while 18 were assigned to a comparison group and continued like normal without any intervention.

Amy D’Amico, director of professional services for the Smithsonian center, said the pandemic made it more difficult to get schools on board. In a world that was changing daily, superintendents were being asked to say yes to hefty commitment — with no guarantee they would receive the new curriculum.

“Typically, people want to be in the intervention group,” D’Amico said. “And we’re asking people to sign on for five years, not knowing what the next week or month was going to look like.”

Lovins said that at first, she was hesitant about participating in the study. The main focus in her fourth grade classroom was to keep her students healthy during the pandemic.

“When school did go back in session, we were in session every other day with half of our students for a long period of time. That mental toll made it challenging to pick up a new curriculum,” she said. “But I’m a huge fan now.”

Many of the schools selected were rural and high-needs, with large numbers of students who were low-income, had Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) or were classified as English learners. In Caldwell County Schools, a district of nearly 11,000 students 70 miles northwest of Charlotte, eight schools participated in the trial, including Hudson Elementary.

Because of COVID-19, the treatment schools didn’t begin to receive professional development until spring 2021. At that point, teachers learned how to implement the curriculum by going through lessons as if they were students.

D’Amico said the professional learning was uncomfortable at first for some of the elementary teachers, because many didn’t have a science background.

“We had to get in and get dirty and use our hands and learn those lessons,” Lovins said. “It’s amazing how many adults are scared of science — scared to teach science, because you’re afraid you’re going to say something wrong — so to be able to get in and use your hands to learn how to teach it made the teachers feel a lot more comfortable about implementing the curriculum in the classroom.”

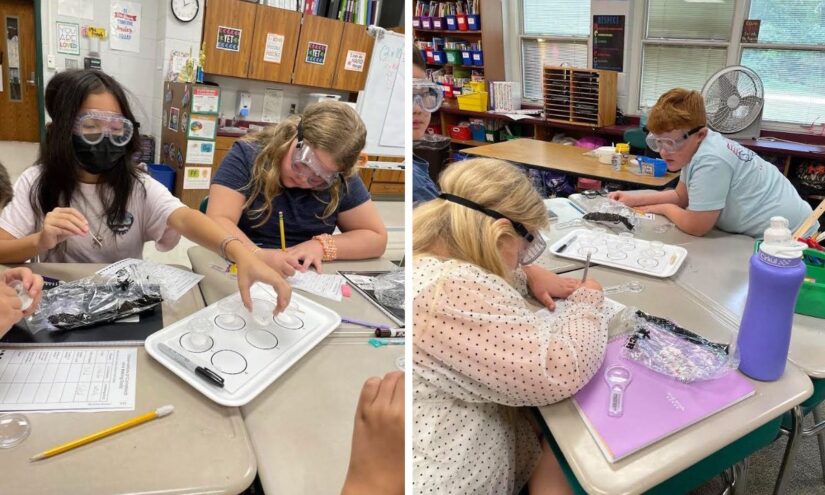

The Smithsonian science curriculum was phenomena-driven, meaning students actively investigate and try to explain real-world events. They collect data, ask questions, experiment with materials and draw conclusions as part of hands-on activities.

In one elementary school lesson, students observed changes in the night sky to figure out how Earth’s orbit around the sun influences which constellations are visible throughout the year.

“If students ask questions about the world around them, you will get students to improve their interest (and) their self-confidence,” O’Donnell said.

Lovins said she noticed over time that as her students used the Smithsonian lessons, they were able to retain information much more easily because they were using their hands to learn abstract concepts. She also saw a lot more joy while teaching science in the classroom.

“They would say, ‘When’s our next science class?’ ” Lovins said. “They were begging for the next lesson because they were having so much fun with the hands-on (activities).”

The University of Memphis Center for Research and Educational Policy evaluated the trial, testing students before and after the study while conducting classroom observations. The researchers evaluated the students’ science achievement with the Stanford Achievement Test (SAT10) while assessing reading and math achievement on state tests.

At the end of the study last year, students in the treatment group showed statistically significant gains in science relative to the comparison group. Overall, the comparison group ranked in the 50th percentile while the treatment group ranked in the 57th percentile in science on the SAT10.

Girls and students of color scored 7 points higher in science than children of the same demographic in comparison schools, while low-income students scored 6 percentile points higher and children with IEPs scored 15 points higher than comparison students with the same demographics.

Students in the treatment group also scored 4 points higher in reading and 6 points higher in math on their state assessments than those in the comparison group, the researchers found.

The results suggest that student achievement in reading and math can improve through science instruction that uses real-world problems, where students have to “read, write, argue from evidence and make calculations,” according to the study’s executive summary.

But it’s not just the curriculum; O’Donnell said it’s important to implement the professional development piece along with it. “Because you would never give teachers just the curriculum — the intervention is the curriculum with aligned professional learning,” she said. “That’s our expectation in the field — that teachers get the support and the development of expertise they need, as well as the materials.”

Lovins said teachers at her school are relearning Smithsonian curriculum this year to continue to implement it next fall.

“It’s so good and it needs to be in every classroom,” Lovins said. “It’s a great program. I hope it stays around.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter