The baby boom reshaped family life and drove population growth in many countries. In this article, we explore the key patterns in seven charts.

The baby boom was a period that saw a surge in birth rates alongside a dramatic decline in death rates due to advances in medicine and public health.

This combination led to rapid population growth in many high-income countries, which influenced their societies for generations.

However, many other aspects of the baby boom are less well-known, including when it began, how marriage rates changed, and how the ages of mothers at childbirth changed.

What were the main patterns of the baby boom? In this article, we’ll explore key data on the baby boom in seven charts.

The baby boom is typically defined as the time period between 1946 and 1964. As an example, Brittanica’s entry on the baby boom states that it describes “the increase in the birth rate between 1946 and 1964”. Similarly, the US Census Bureau defines baby boomers as “those born between 1946 and 1964”, with the common belief that the baby boom started immediately after World War II.

But as the chart below shows, the rise began earlier.

Birth rates in the United States had been falling in the early twentieth century, and the decline began to slow down at the end of the 1920s. Then, in the late 1930s, they turned around and began to rise, and this continued during parts of World War II. At the end of the war, they surged, but this was part of a multi-decadal increase.

One of the striking aspects of the baby boom is that it happened in many countries at the same time.

Many high-income countries saw a rise in birth rates — it wasn’t just nations directly involved in World War II. Sweden and Switzerland did not actively participate in the war, but they also experienced significant increases in birth rates. You can see this in the chart below.

Several countries — such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and the United States — began to see a turnaround in birth rates before the war. In many others, it occurred during the war.

This common trend across many countries suggests that the baby boom was driven by shared societal shifts rather than isolated national circumstances.

The causes of the baby boom are still widely debated by demographers. Various theories have been put forward, including the role of economic factors, such as rising wages and opportunities, and lower housing costs, as well as declining maternal mortality and societal changes.2

The baby boom was also surprising because it happened alongside rising levels of women’s education and workforce participation — changes that often coincide with falling birth rates.3

It’s likely that multiple factors played a role and that no single explanation fully accounts for the surge in births. Although we don’t know the full story, in the following sections, we’ll explore some of the pieces that shaped this remarkable demographic shift.

Starting in the 1930s, marriage became more common.

The chart below shows the large rise in marriage rates among women between the ages of 20 and 24.

In 1930, around 54% of young American women of this age were married.4 By 1960, this had increased to 72%.

In England and Wales, the share who were married more than doubled: from 26% to 58%.

Research suggests that the baby boom across countries was primarily driven by higher marriage rates and less by married couples having significantly more children overall.5

During the baby boom, women not only had more children than the previous generation but also started their families earlier.

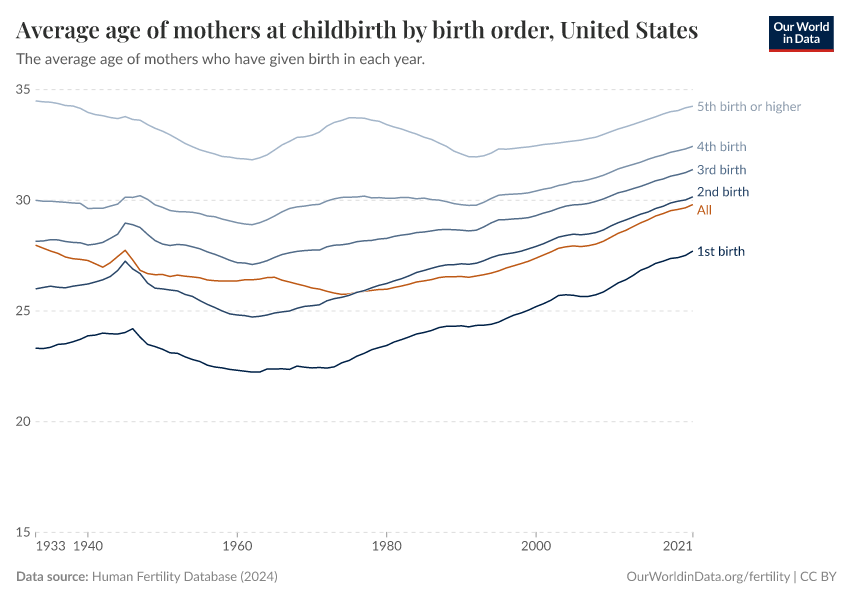

The chart here shows the average age of women at childbirth.

If you look at the red line, you see that in 1933, the average age of American women giving birth was 28. At the time, birth rates were slowly increasing, and until the early 1940s, the average age was gradually declining. However, during World War II, some women delayed having children, which caused the average age at childbirth to rise slightly.

However, once World War II ended, women began having children earlier, especially for their first and second births, and the average age at childbirth dropped. This pattern of starting families earlier continued through the baby boom years and lasted until the mid-1970s. Since then, the age of mothers has risen gradually and continuously. In 2021, the average age was 30.

Again, this trend is similar in other high-income countries, as you can see by switching the chart to different countries.

How did the baby boom shape birth patterns for different generations of women over their lifetimes?

This chart can look complicated at first, but it helps us answer these questions by showing how the timing and number of births changed across cohorts of women in the United States.

Each curve on the chart represents birth patterns among women born in a specific year. By following a curve from left to right, you can see when women born in a particular year had children.

The height of the curve represents the number of births per woman at that age. This means that birth cohorts with taller curves had higher birth rates at that particular age.

Before the baby boom, women had children at a broader range of ages, often spreading births from their twenties into their late thirties and early forties.

We see a clear shift for women born in the 1920s and 1930s — many of whom gave birth during the peak of the baby boom — as childbirth became more common in the twenties and early thirties.

The chart also shows a diagonal ridge, a striking surge in births, which corresponds to the year 1946, and shows women’s ages in that year. For example, there is a rise in fertility rates among 26-year-old women born in 1920 and 21-year-old women born in 1925 — reflecting the year 1946.

Birth rates surged during the baby boom as more couples married and started families, creating a noticeable peak in the timing of childbirth for women during this era.

Women born in the 1950s and 1960s mostly had children in their twenties and early thirties, meaning the age range at childbirth narrowed.

Then, for women born in later decades, the range grew again.

Recent cohorts of women have children across a much broader range of ages, with many delaying childbirth into their late thirties and early forties. You can see this at the bottom of the chart.

We can also look at the total number of births women had over their childbearing years in each generation.

This is measured by the “completed cohort fertility rate”. It’s given by the woman’s birth year.7 The data ends in 1971 as recent generations of women have yet to complete their childbearing years.

Let’s look at women born from the 1910s onwards who had children during the baby boom.

As you can see, the cohort fertility rate — the average number of births per woman by the end of her childbearing years — rose for these cohorts of women. It peaked at an average of more than 3.2 births per woman.

This shows us that the baby boom not only changed the timing of births but also raised the total number of children women had.

Did the average number of children increase because women were having more children than in the past? Or because fewer women had no children?

The data tells us that it was both.

This chart explores the data: it shows the share of women in each birth cohort who had zero, one, two, three, or four or more children during their lifetimes.

Around two-fifths of women born in 1918 had had three or more births, while around a fifth had no children.

At the peak of the baby boom years — women born in the late 1920s or early 1930s — three or more births became the norm, and almost 40% had four or more.

For those born in the late 1930s, the trend began to reverse.

The share of women having three or more children started to decline. Two became the typical number of children in many high-income countries.8

The chart also shows that it became less common for women to have no children across their lifetimes.

Having no children was relatively common for women born in the early 1900s, with about 18% having no children.

As we move to the baby boom cohorts, born in the 1920s and 1930s, this figure sharply declined. For those born in the late 1930s, only about 6% of women had no children.

The trend reversed for women born after the late 1930s, and the share of women with no children steadily rose through the 1940s and 1950s cohorts. For women born in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it reversed again.

When we think of the baby boom, we often imagine a surge in births in the United States starting at the end of World War II, as soldiers returned home and families began to grow.

But although this is part of the story, the trend is much broader, as we’ve seen in this article.

Birth rates were already on the rise in the 1930s, setting the stage for an even bigger increase in the 40s and 50s. The baby boom wasn’t just a post-war phenomenon; it was part of a broader trend that spanned multiple decades.

Women born during the baby boom years had more children, and family sizes grew larger than in earlier or later generations.

After the baby boom period, families started to shrink, and childbirth became concentrated in a narrower range of ages, primarily in women’s twenties and early thirties.

Over time, however, this compressed pattern of family formation began to change again. Recent generations of women have had children across a much broader range of ages, from their twenties through their forties.

The data also show that cohort fertility rates — the total number of children born to women over their lifetimes — rose again among women born in the 1960s, reversing earlier declines.

A combination of higher birth rates and lower death rates led to a period of rapid population growth, which profoundly shaped the economies, societies, and cultures of high-income countries.

By looking closer at how birth patterns shifted — when women had children, how many they had, and the broader societal changes that shaped these trends — we have a clearer picture of the baby boom and how it reshaped family life for the generations that followed.

Acknowledgements

Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, and Edouard Mathieu provided valuable feedback that helped improve this article.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Saloni Dattani and Lucas Rodés-Guirao (2025) - “The baby boom in seven charts” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: 'https://ourworldindata.org/baby-boom-seven-charts' [Online Resource]BibTeX citation

@article{owid-baby-boom-seven-charts,

author = {Saloni Dattani and Lucas Rodés-Guirao},

title = {The baby boom in seven charts},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/baby-boom-seven-charts}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.