Problems with a huge database of voter information that effectively functions as the central nervous system of the Democratic Party grew so worrisome last summer that top Democrats staged an extraordinary intervention to keep it running through the November election, according to multiple people involved.

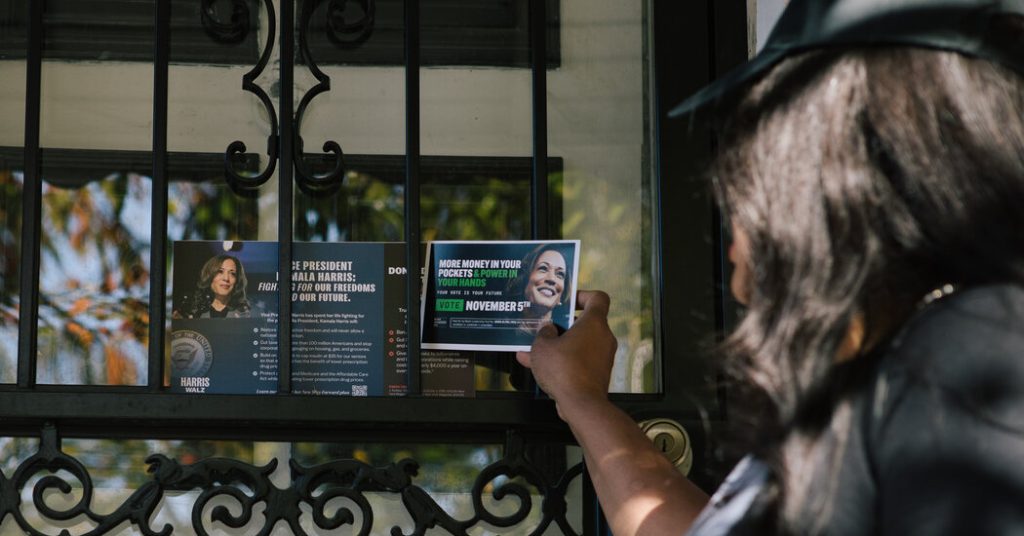

Had it collapsed, the party’s entire get-out-the-vote operation could have been temporarily crippled, forcing canvassers to work with pen and paper instead of smartphones, and leaving campaigns effectively blind — unaware of which doors to knock on and which phones to call.

To avoid such a catastrophe, a handful of engineers from the Democratic National Committee and the Kamala Harris campaign scrubbed in, spending months to ensure the database stayed afloat, the people said.

The private company that runs the database warned some Democratic groups that it could not handle the large volume of data being uploaded and downloaded. An outside entity raced to install a workaround, while a wealthy Democratic financier, Allen Blue, was asked to fund an emergency engineering operation to keep data flowing.

“This can’t happen again,” said Mr. Blue, a founder of LinkedIn, who warned that an overhaul of the party’s technological infrastructure needed to be part of any broader Democratic rebuilding efforts. “Technology and data are the foundations for how modern campaigns are run.”

The episode, which has not been previously reported, has deepened concerns at the party’s highest levels about its singular dependency on a for-profit company whose majority owner, a private equity firm, has imposed layoffs in recent years to slash costs.

The company insists the database worked fine.

This week, as a group of Democratic tech operatives gathered in Puerto Rico to discuss the future of data and technology for the party, the fate of the database system, called NGP VAN, was on the agenda.

And on Wednesday, a group called the Movement Cooperative, a nonprofit that provides data and technology support to progressive groups, solicited proposals for the construction of a new voter data system that is being discussed as a possible alternative to NGP VAN.

Michael Fisher, who joined the Harris campaign last summer to ensure the reliability of its technology, said the database had been wheezing for years and required an enormous and distracting level of attention just to function in 2024.

“This can’t be a conversation in another four years,” Mr. Fisher said, urging Democrats to set up a new database. “The only reason I’m talking to you is this is the moment it can change.”

Now, the Democratic National Committee is considering just that. Officials are mulling something of a nuclear option — invoking a clause buried in the party’s contract with the database’s owner to demand a copy of the source code, according to two people with knowledge of the conversations who insisted on anonymity to describe them.

The committee declined to answer questions about its plans.

“The Democrats’ technology infrastructure ensures we’re ready to win elections up and down the ballot both right now and for years to come, including with significant safeguards and redundancies so that our data is secure, accessible, and Democrats are never caught in a lurch,” Arthur Thompson, the chief technology officer for the D.N.C., said in a statement, calling it a top priority of the party’s new chairman, Ken Martin. “We’ll be evaluating every relationship we have with vendors to make sure they all meet the moment.”

Mr. Thompson was among the party’s tech operatives meeting in Puerto Rico.

Chelsea Peterson Thompson, the general manager of NGP VAN, who is not related to Mr. Thompson, pushed back on descriptions of the product as faltering, describing it in a statement as “the gold standard of political organizing tools.”

She suggested an ulterior motive for the criticism.

“It is not surprising or new that detractors in the space want the opposite to be true as it would benefit their own personal or commercial ambitions,” Ms. Thompson said, adding, “The platform enabled the largest voter outreach program in human history without stability or downtime issues.”

And she denied that the platform was ever near failing — “Not close at all,” she said — saying the final weeks before the election had been “remarkably calm.”

The company, which traces its origins to the late 1990s, is called NGP VAN after the 2010 merger of a company that specialized in political fund-raising, NGP Software, and the Voter Activation Network, which focused on contact with voters.

The VAN, as most Democrats call it, contains billions of records amounting to nearly every piece of information the party has collected about tens of millions of Americans. Virtually every Democratic-aligned campaign or group can access those records and put the information to work to persuade, organize or mobilize voters.

As the saying goes among party operatives: “If it’s not in VAN, it doesn’t exist.”

NGP VAN was purchased as part of a $2 billion deal in 2021 by a private equity firm, Apax Partners, which created a subsidiary called Bonterra that now oversees the company.

(The Republican Party also relies on a for-profit company, Data Trust, to house its voter files. But Data Trust has remained largely under the control of party-aligned operatives since its inception nearly 15 years ago.)

Democratic officials have complained publicly and privately about the damaging impact of cost-cutting, layoffs and underinvestment since the purchase. An internal Democratic National Committee memo in early 2023, obtained by The New York Times, warned that VAN’s infrastructure was already “inflexible, slow and unreliable, particularly during periods of peak use.”

“It is likely that Bonterra will continue to cut costs and move development resources away from the core tools used by Democratic campaigns,” the memo predicted.

By early 2024, concerns had grown serious enough that the D.N.C. held internal discussions about exercising the source-code clause, which would have allowed it effectively to take its data elsewhere. The committee drafted a letter from its executive director, Sam Cornale, to Bonterra’s chief executive, which cited concerns about the database’s stability and the support it was receiving from the company. The draft said the D.N.C. needed the code to “help safeguard the Democratic Party’s interests against potential risks during this period of uncertainty.”

The letter was never sent. Party officials and the re-election campaign of Joseph R. Biden Jr. — which did not have its own chief technology officer — ultimately determined such a drastic move could backfire in the middle of an election year.

They decided to take their chances on sticking with NGP VAN.

Even so, a group of Democrats concerned about the system’s reliability — after the 2020 Biden campaign had experienced problems with it at times — built a backup plan through an entity called the Movement Infrastructure Group. It effectively created a side door to move large volumes of data into and out of the NGP VAN system.

Fears of a meltdown of the NGP VAN system grew last summer after Ms. Harris became the Democratic nominee for president, when the company warned her campaign and the D.N.C. that its canvassing app was not ready to meet the demand the campaign was projecting, according to two people with knowledge of the situation.

From that point through the election, the Harris campaign and the D.N.C. had technical experts working full time to help keep NGP VAN’s tools functioning, the people said.

Still, in October, Mike Pfohl, the president of Empower Project, a progressive nonprofit that does organizing work, said he was “shocked” to be asked by NGP VAN to cut back on the information his group was adding to and extracting from the database.

“We were told we were generating too much traffic to them and had to throttle the amount the data we were sending to them so we didn’t crash anybody else,” Mr. Pfohl said.

Ms. Thompson, the general manager of NGP VAN, said only a handful of software vendors — who had planned to make “thousands of requests per second” of the database, “in excess of our industry standard and publicly posted” rate limits — had been affected. She said NGP VAN had worked with those groups to address their needs.

Mr. Pfohl said that his organization was able to manage, but that the throttling could have been devastating for others. And he spoke disdainfully of NGP VAN’s private-equity ownership, saying that the profit motive was at odds with the database’s reason for existence in the first place.

“The mission should be the mission,” he said. “The idea that we would be taking dues from union members to help someone eventually buy a yacht makes my blood boil.”