This story was co-published with The Guardian.

In 2020, when Amy Coney Barrett came before the Senate for confirmation to the U.S. Supreme Court, one of her closest friends told a story on TV about their year together working as law clerks in the nation’s capital.

“That last day when you leave the court, you think, ‘Wow, that’s about the coolest thing that’s ever going to happen to me,’” said Nicole Stelle Garnett. She assisted Justice Clarence Thomas during the 1998 term, the same year Barrett worked under Justice Antonin Scalia. “Now, to see my friend testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee, to walk back up the steps 21 years later is really, really something.”

Fast forward another five years. Garnett, now a law professor at the University of Notre Dame, is about to have her own Supreme Court moment.

On April 30, the court will consider a legal question that has defined her career: Can explicitly religious organizations operate charter schools? At the center of the dispute is St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, an online school in Oklahoma that planned to serve about 200 students this year before the state supreme court ruled the decision to approve it violated the constitutional provision separating church and state.

“This could be an earthquake for American public education,” said Samuel Abrams, who directs the International Partnership for the Study of Educational Privatization at the University of Colorado, Boulder. As the country experiences a rise in Christian nationalism, a favorable ruling could invite the encroachment of religion not only into education but other areas of civic life that have traditionally been non-sectarian. “If the Supreme Court rules in favor of overturning that decision, the church-stage cleavage will disappear. That’s a dramatic development for the First Amendment.”

In a sign of the case’s gravity, the Trump administration filed a brief in support of St. Isidore last week, arguing that “a state may not put schools, parents or students to the choice of forgoing religious exercise or forgoing government funds.”

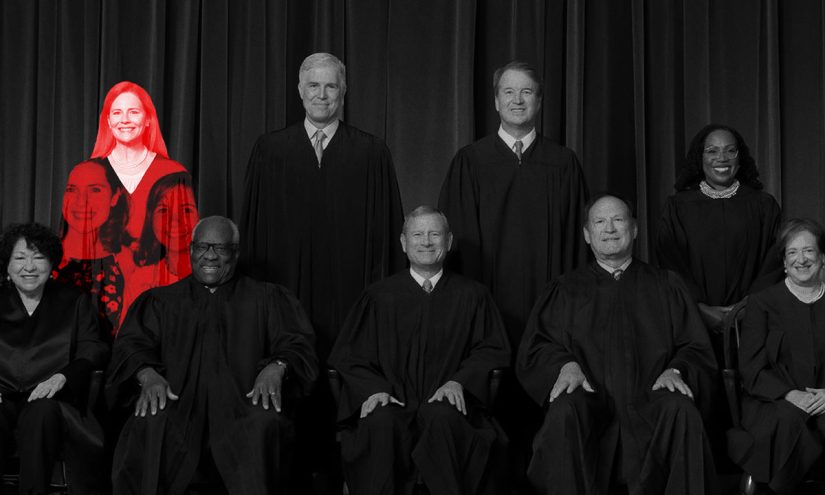

But Barrett, who handed President Donald Trump a conservative 6-3 supermajority when she was confirmed to the court, won’t be on the bench to hear it. She recused herself, leaving no explanation for sitting out what could be the most significant legal decision to affect schools in decades.

Observers believe the reason is her friendship with Garnett, who was an early legal adviser to the school. While she’s not officially on the case and hasn’t joined any legal briefs in support of it, Nicole and her husband Richard Garnett, also a Notre Dame law professor, are both faculty fellows with the university’s Religious Liberty Clinic, which represents St. Isidore.

In a deep irony, the longtime friendship between the two women, forged in Catholic faith and a conservative approach to jurisprudence, now threatens to tip the scales away from a cause Garnett has spent her career defending,

The recusal increases the chances that the vote could end in a 4-4 tie, which would leave the Oklahoma court’s decision intact. That outcome would prohibit St. Isidore from receiving public funds and likely send proponents of religious charters looking for a new test case.

Justices typically do not offer reasons for recusing themselves. A spokesperson for the Supreme Court said Barrett had no comment on the matter.

“I feel bad for Nicole,” said Josh Blackman, an associate professor at the South Texas College of Law in Houston. “This is her life’s work, and it might go to a 4-4 decision.”

Blackman, a proponent of religious charter schools, has known the Garnetts for years. “Amy knows what Nicole did for this case,” he said. “The case is so significant because it’s an application of both [the Garnetts’] Catholic faith and their views on constitutional law.”

‘A heady experience’

The friendship between Garnett and Barrett developed long before the legal clash over St. Isidore. When Trump nominated Barrett to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Garnett relayed how the two first met at a coffee shop the spring before they became high court clerks in the late 1990s.

“I walked away thinking I had just met a remarkable woman,” she wrote in a commentary for USA Today.

There weren’t too many high-profile cases that year, Garnett said. But one stands out — a complaint that a Chicago ordinance against gang loitering violated members’ due process rights. The court ruled against the city, but Barrett and Garnett performed research for dissenters Scalia and Thomas. Thomas said the local law allowed police officers to do their jobs and Scalia called it a “small price to pay” to keep the streets safe.

“It’s a heady experience and really hard work,” Garnett told The 74. “But we all liked each other. We socialized together.”

When Trump nominated Barrett in 2017 to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, all 34 clerks from the Supreme Court class of ‘99 — Democrats, Republicans and independents — wrote a letter of support to the Senate judiciary committee.

But none knew Barrett like Garnett. Their personal and professional lives have been intertwined for more than two decades.

When Garnett was pregnant with her first child during their year as clerks, Barrett and the other young attorneys threw her a baby shower in the court’s dining room for justices’ spouses. Barrett is godmother to the Garnetts’ third child. After their clerkship, Richard Garnett helped recruit Barrett to the boutique Washington law firm where he worked. (He later recruited Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, one of the court’s three liberals, to the same firm.)

Before Barrett cast her vote for the majority in the 2022 decision that struck down Roe v. Wade, the New Yorker published a profile that described the newest justice as a “product of a Christian legal movement” shifting the court further to the right. The article irked Garnett’s daughter, Maggie, who said it dismissed “a mentor and maternal figure in my life” as a “cold, impenetrable” mouthpiece for conservatives. In a robust defense, she wrote that the article portrayed Barrett as “an almost robotic product of her male mentors … rather than as an accomplished and talented jurist in her own right.”

At Notre Dame, Garnett and Barrett overlapped as faculty members for roughly 17 years. Aside from her focus on religious liberty and education, Garnett also teaches property law. Barrett’s courses focused on constitutional law and the federal courts.

“She became a lifelong friend,” Garnett said. “She lived around the corner from us and we raised our kids together.”

And when Trump introduced the mother of seven to the nation, Garnett was seated in the Rose Garden along with senators, White House officials and other dignitaries.

Given their intersecting interests, it’s very likely that school vouchers came up in conversation. Until 2017, Barrett served as a trustee at Trinity School at Greenlawn, a classical Christian academy in South Bend, Indiana, that participates in the state’s private school choice program.

Garnett, meanwhile, was honing legal arguments in favor of expanding such programs. Before joining the faculty at Notre Dame, she worked as a staff attorney for the Institute for Justice, a right-leaning law firm that has led efforts to open school choice programs to religious schools. In one case, the Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the expansion of Milwaukee’s voucher program to include faith-based schools.

While at the institute, Garnett also worked on Bagley v. Raymond, which challenged Maine’s exclusion of religious schools from a private school choice program. The state won that case, but lost when a subsequent case about the program, Carson v. Makin, came before the Supreme Court. In Carson, Barrett joined the other five conservative justices in ruling that it was unconstitutional to keep those schools out.

Garnett, who didn’t work on Carson, said she cried when the family at its center won.

But even with this victory, Garnett viewed aspects of school choice as unfriendly to religious freedom. She found it troubling that to keep their doors open, many Catholic schools in Indiana were converting to charters, which required them to remove all evidence of their faith.

“Religion has been stripped from the schools’ curricula and religious iconography from their walls,” she wrote in a 2012 paper. “There is little doubt that the declining enrollments in Catholic schools are at least partially attributable to the rise of charter schools.”

Her convictions on the role of religion in public life are both personal and professional. She sent her children to Catholic schools in South Bend and views their mission to serve low-income children as vital to urban communities. She captured her years of scholarship on religious liberty in a line she wrote after Carson: “The Constitution demands government neutrality toward religious believers and institutions. Full stop.”

That view is belied by state laws that prohibit public funds from directly supporting religious schools and that define charters as public schools open to all students. Some critics predict that religious groups running charters would not have to uphold the civil rights protections of LGBTQ students, for example.

Garnett warned that attempts to create religious charters would face litigation for years. But in Oklahoma, Republicans and Catholic church leaders were ready for a fight.

At a time when schools remained shuttered due to COVID, Catholic school leaders in Oklahoma City and Tulsa wanted to expand virtual options and “reach more kids in a big rural state,” she said. A widely-circulated 2020 paper she wrote for the right-wing Manhattan Institute offered a legal path to get there.

“I think that we found each other,” she told The 74. “I didn’t go looking for a client here. It’s very organic how the whole thing unfolded.”

‘Hot ticket’

If other recent school choice cases are any indication, there’s still a good chance the court will overturn the Oklahoma Supreme Court’s opinion. Such a precedent-setting development would have a huge impact on the nation’s educational landscape, said Michael Petrilli, president of the conservative Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

The court could say that “a charter school authorizer can’t turn down an otherwise qualified applicant just because it is religious, or proposes a religious school,” he said. “That would apply immediately to all states with charter laws on the books.”

Garnett dismissed the idea that a victory for St. Isidore will open the floodgates to thousands of religious schools becoming charters. Applicants would still have to meet state criteria for approval, she said.

The ruling “may shed light on other state’s arrangements, but it definitely will not require all states to allow religious charter schools,” she said. “That’s not on the table — and it’s not how the court works.”

But others are not so certain.

“The implications for education and society could be profound,” said Preston Green, a University of Connecticut education professor. “It would mean that the government cannot exclude religious groups from any public benefits program.”

With oral arguments approaching, Notre Dame law students who have worked with Garnett over the past two years have already asked if she can get them a seat in the courtroom for such “a hot ticket,” she said.

She won’t talk about why her friend recused herself from the case, but acknowledged the stakes.

“My hope is that it won’t go to a 4-4,” Garnett said “My hope is that they wouldn’t have granted [a hearing] if they thought it might. But I know you don’t make assumptions about anything.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter