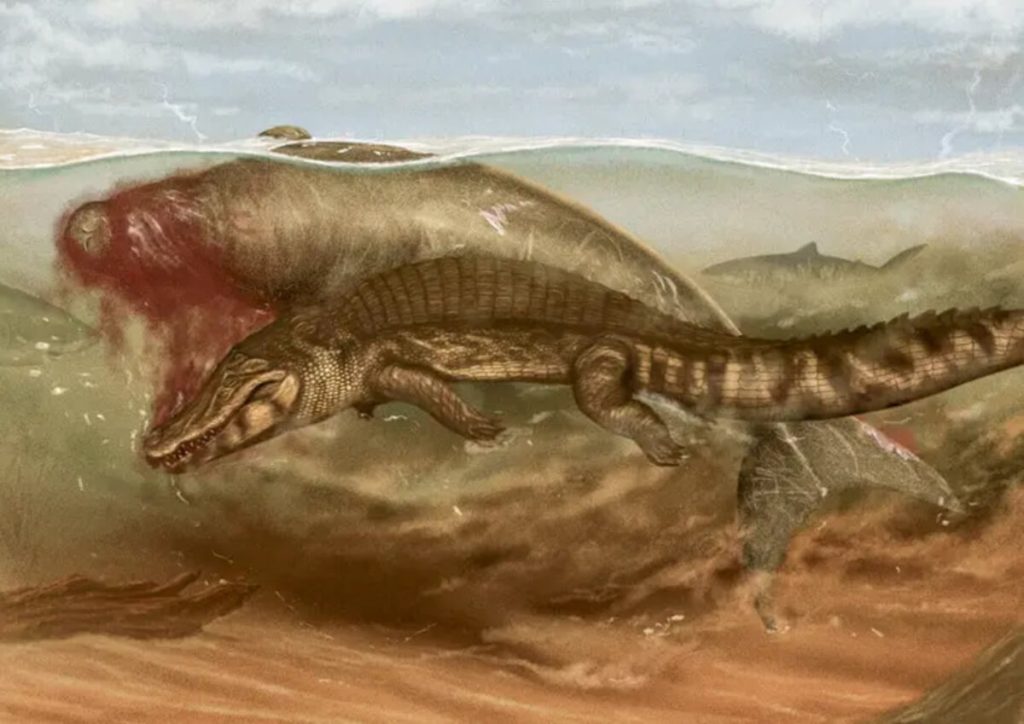

Illustration of a sea cow being attacked by a crocodile. (Credit: Jaime Bran Sarmiento)

The remains of a prehistoric sea cow tell story of multiple predator attacks

In a nutshell

- A remarkable fossil discovery in Venezuela preserves evidence of both crocodilian predation and shark scavenging on a single ancient sea cow, offering a rare glimpse into prehistoric marine food webs. This type of multiple-predator interaction is seldom found in the fossil record.

- The specimen’s excellent preservation in fine sediments allowed scientists to identify different types of bite marks, including deep tooth impacts suggesting the crocodilian tried to drown its prey – similar to hunting strategies used by modern crocodiles – while scattered shark bite marks indicate later scavenging.

- The discovery began with a local farmer noticing unusual rocks, leading to a new fossil site 100 kilometers from previous finds. The careful excavation took a team of five people seven hours to complete, followed by months of detailed laboratory preparation, highlighting the meticulous nature of paleontological research.

ZURICH — Some fossils tell simple stories. But a recent discovery in Venezuela tells a more complex tale, preserving evidence of multiple predator attacks on an ancient sea cow in what amounts to a detailed snapshot of prehistoric marine life. What started as a local farmer’s observation of odd-looking rocks has become a significant window into ancient ecology.

The study, published in Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, analyzed the fossil to uncover what happened to this fossilized sea cow millions of years ago. When paleontologists unearth fossils, they typically find only fragments that hint at how ancient animals lived. But occasionally, they strike gold. The find, located 100 kilometers away from previous fossil sites, is helping researchers understand prehistoric marine food webs in unprecedented detail.

“Today, often when we observe a predator in the wild, we find the carcass of prey, which demonstrates its function as a food source for other animals too; but fossil records of this are rarer,” says lead researcher Aldo Benites-Palomino from the University of Zurich, in a statement.

The discovery required painstaking work to uncover. A team of five people spent seven hours carefully extracting the fossil using specialized techniques with full casing protection. Subsequent laboratory preparation, particularly the delicate work of preparing and restoring the skull elements, took several months.

M2–M3 in occlusal view. D, E, skull fragments include the rostrum, F, G, dentary, and H, I, basicranium. (Credit: Benites-Palomino et al., Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

The ancient victim belonged to a group called Culebratherium, distant relatives of today’s manatees and dugongs. Modern sea cows are basically the cows of the sea—slow-moving vegetarians that spend their days grazing on underwater plants. Like their modern cousins, this ancient sea cow had dense, heavy bones and thick layers of fat, making them easy targets for predators.

The fossil specimen, found in rock layers from Venezuela’s Agua Clara Formation, includes parts we might think of as the animal’s head and neck region, specifically, a partial skull and 18 vertebrae. The excellent preservation of the fossil’s outer bone layer, attributed to the fine sediments in which it was embedded, allowed researchers to observe clear evidence of predation.

The scientists identified two different types of bite marks telling different parts of the story. Some marks look like round punctures with slightly rough edges, while others appear as curved gouges with deep starting points. These marks match what scientists see when modern crocodilians bite their prey. These “conspicuous” deep tooth impacts concentrated on the sea cow’s snout suggest an attempt to suffocate the prey, which is a hunting strategy still used by modern crocodiles.

The second type of damage appears as long, narrow cuts with triangular cross-sections – the telltale sign of shark bites. The discovery of a tiger shark (Galeocerdo aduncus) tooth in the sea cow’s neck region, along with scattered bite marks throughout the skeleton, indicates that sharks scavenged the remains after the crocodilian attack.

tearing marks. D, reconstruction of the trophic interactions by Jaime Bran. E, shark bite marks in the ribs, and F, detailed view. G, associated Galeo

cerdo aduncus tooth in labial view. (Credit: Benites-Palomino et al., Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology)

“Our previous research has identified sperm whales scavenged by several shark species, and this new research highlights the importance of sea cows within the food chain,” says Benites-Palomino.

While the fossil record contains evidence of such food chain interactions, they are usually represented by fragmentary fossils with difficult-to-interpret marks. This discovery is particularly valuable because while we know the ancient Caribbean was home to many species of sea cows, their fossils are rarely found in Venezuela. Co-author professor Marcelo R. Sanchez-Villagra, director at the Palaeontological Institute & Museum at Zurich, describes the find as “remarkable,” particularly given its unusual location.

The discovery adds to growing evidence suggesting that marine food chains millions of years ago operated similarly to those we observe today, with predators and scavengers playing distinct but interconnected roles in their ecosystems. This 15-million-year-old specimen provides a rare glimpse into these ancient ecological relationships, documented through the preserved remains of predator-prey interactions.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The discovery process began when a local farmer noticed unusual rocks in an area 100 kilometers from known fossil sites near Coro, Venezuela. After investigating the site and consulting geological maps to determine the age of the rocks, researchers organized a careful excavation. A team of five people spent seven hours extracting the specimen using specialized techniques with full casing protection to preserve the delicate remains. The fossil preparation was particularly meticulous, with several months dedicated to preparing and restoring the cranial elements. The research team focused on analyzing large, well-preserved bite marks, made possible by the exceptional preservation of the fossil’s cortical layer due to the fine sediments in which it was embedded. They categorized the bite marks into three types based on shape, depth, and orientation, comparing them to known patterns of predation from modern and fossil examples.

Results

The team identified three distinct types of bite marks: shallow round pits with semi-circular outlines (Type A), wider curved incisions with deeper starting points (Type B), and long narrow slits with triangular cross-sections (Type C). Types A and B were attributed to crocodilian attacks, particularly concentrated around the snout area, suggesting an attempt to suffocate the prey. Type C marks were identified as shark bite marks, scattered throughout the skeleton. The discovery of a Galeocerdo aduncus tooth near the sea cow’s neck provided definitive evidence of shark scavenging. The excellent preservation of the fossil’s outer bone layer, due to the fine sediments in which it was found, allowed researchers to observe these predation marks in exceptional detail.

Limitations

While the specimen’s preservation in fine sediments helped maintain important surface details, the fragmentary nature of the specimen and the loss of some cortical bone due to preservation issues limited the team’s ability to identify all possible bite marks. The researchers note that alternative scenarios for how these marks were made cannot be completely ruled out due to the specimen’s incomplete preservation. Additionally, the team had to spend considerable time determining the site’s geology and age, as this was a previously unknown fossil locality.

Discussion and Takeaways

This study provides one of the few documented cases of multiple predators interacting with a single prey item in the fossil record. The location of the site, 100 kilometers from previous fossil finds, expands the known range of these ancient marine mammals in the region. The exceptional preservation conditions, attributed to the fine sediments, allowed researchers to observe predation marks in unusual detail, providing strong evidence for both active predation and scavenging behaviors. The discovery also expands our understanding of sirenian diversity in the Southern Caribbean and offers insights into the trophic relationships during the Early to Middle Miocene in the proto-Caribbean region.

Funding and Disclosures

The research was supported by various institutions, including the Museo Paleontológico de Urumaco and the Alcaldía Bolivariana del Municipio Urumaco. The Instituto del Patrimonio Cultural de Venezuela (IPC) issued permits for prospection and collection of fossils in the Falcón State (IPC permit no. VE-IPC-CEBC-06/2022-1). Current research at the University of Zurich led by the first author benefits from a Candoc Grant (K-74603-06-01).

Publication Information

This study was published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (Volume 43, Issue 6) in 2024, authored by Aldo Benites-Palomino, Gabriel Aguirre-Fernández, Jorge Velez-Juarbe, Jorge D. Carrillo-Briceño, Rodolfo Sánchez, and Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra. The article has received significant attention, with over 6,500 views at the time of publication.