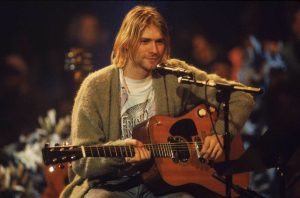

A star-streaked sky, the undulant surface of the sea, a gooseneck lamp, a glowing electric heater, the delicate architecture of a spiderweb, a Porsche cruising along a California freeway—these are some of the subjects that have captured the vivid attention of Vija Celmins. For more than half a century, the Latvian-born, US-raised artist has produced absorbing paintings and drawings that are often inspired by—and mistaken for—photographs. “The image is just a sort of armature on which I hang my marks and make my art,” she has said of her work, which is born of hallucinatory concentration and, in her view, never truly complete. Pieces are worked on and reworked, again and again, becoming less about depiction and more a record of mark making that describes the passage of time.

For Aperture’s spring issue, Celmins spoke with the photographer and her friend Richard Learoyd, who is, likewise, known for a decelerated, highly technical approach that gleans meaning from the limits of representation, in his case by using a camera obscura to create crisp, hyperreal portraits and still lifes haunted by the history of painting. The two artists discuss Celmins’s philosophy as an artist, falling in love with gray, and the rewards of slowness.

Courtesy the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Richard Learoyd: I’ve looked at quite a bit of your pictures over the years, and it seems that photography is useful to you in some way. Do you think that’s true?

Vija Celmins: Well, you know, I am not really that interested in photography.

Learoyd: We know that!

Celmins: When I was really young and in school, I wanted to be an abstract painter, of course, because that was a going thing. I think that I agreed that the painting was about itself. But I was unable to really make the marks that were just marks, to build a space that I thought was the proper space. I couldn’t incorporate that two-dimensional plane, which is very important as a reality; it is not just a support, it is what keeps you out of the work and invites you in at the same time, because of the convention of hanging these two-dimensional things on the wall.

Learoyd: It’s a pictorial gravity, isn’t it? It’s something that draws you toward it and pushes and repels at the same time.

Celmins: Right. First of all, as you can probably tell, I’m not a big colorist. But I did try to make de Kooning paintings the best I could when I was in school because that was heroic art for me. I think I liked the fact that he was a European, that he came here, that he was sort of lost, then started all over again, and that he also had some skill in drawing. I had been drawing since I had come to the United States, not being able to speak English, and was put in school. I drew, and they left me alone because I couldn’t speak.

Learoyd: Where did you first arrive?

Celmins: We were brought by the Church World Service to the United States and put in a hotel until somebody who wanted to take in refugees after World War II signed up for us. And somebody did—unfortunately, in Indianapolis. I was nine when I came. I taught myself to speak. I used to go to the library and get first-grade books, although I could read a total book in Latvian. I was kind of a loner, which I still probably am.

Somehow, I got fascinated with art, but in a primitive way, let me tell you. I drew all the things that girls drew, like horses, movie stars. Somehow, it made a kind of life. When I was in high school, I happened to be the person that drew. If anybody needed anything, they pointed to me. I got into that mode like it was my life. So, I started getting a little more sophisticated and looking at paintings, and then I went to art school.

Learoyd: At that point, were your parents taking you to museums or galleries?

Celmins: No, no. Never been to a museum till I was in high school. I think they had a class in a museum, but I didn’t even realize what that was.

We sang all the time at home, with other people, and in the church. See, I never really understood the church. I’m not a religious person. But somehow, I stumbled into this world. I didn’t yet realize the complication of making something that you cannot explain.

Learoyd: Well, it’s the enigma, isn’t it?

Celmins: Right.

Learoyd: Which is the problem.

Celmins: Which is what we’re dealing with right here. It’s like making something that is full and meaningful but not accessible with words. You have to experience it.

Vija Celmins, Untitled (Source Materials), 1999. Iris print on paper

Vija Celmins, Snowfall (coat), 2021–23. Oil on canvas

Learoyd: My personal experience is very different, but also similar in the fact that I was never dragged around museums and galleries and things as a kid. I was aware that those things existed, because television existed. You went to art school when you were how old?

Celmins: I got out of high school, and I got these scholarships for art school. My parents were both working and poor. I went. I found my set of people. My people who all ended up in art school because of something that attracted them, or because they were already good, or whatever. At that time, women weren’t supposed to be smart. I don’t know what the problem was in the ’50s, you know? I really liked science a lot, but it never occurred to me that I could also learn things that were very valuable, about how life turns . . . I used to catch bugs myself, and sometimes cut them apart to look at them, but I never really had that training, which is too bad. So, I was sort of funneled into the two-dimensional plane. Ha ha.

Learoyd: What I felt was that my life began when I started making photographs, because it was the only thing I was good at. I wasn’t even good at it at the time, but I was interested. And then what I found was that other adults, besides my parents, became interested in me.

Celmins: Yes. That happened, of course, to me too. My parents totally ignored me. I had to make my own relationships and so forth. When you started, did somebody give you a camera? You see, I never had a camera.

Learoyd: I used to look at magazines with pictures of cameras, and I thought they looked sort of cool.

Celmins: I like that. That’s great, thinking, What is that? You can make pictures out of this thing.

Learoyd: Yeah, they looked cool. I didn’t have a clue what to do, because I was terrible at everything. You eventually moved to LA, right?

Celmins: I moved to LA because I got a scholarship. Before that, I got a scholarship to Yale, at that summer school, where I met probably my favorite artist my own age, who was Brice Marden. He was so good right off the bat.

Then I went back to Indiana, and I tried to paint these big abstract paintings. Now they look very thin, because I never really saw the relationship of that plane. I know it sounds kind of old-fashioned, nobody thinks like this anymore.

Learoyd: What do you mean, thin?

Celmins: They were abstract blobs and lines and trying to make a structure that stayed on the canvas. Then when I went to LA, I kept that up. But I got to where I needed some other kind . . . I think I started doing landscapes.

Learoyd: What sort of landscapes?

Celmins: Oh, from California. I didn’t have enough money to buy canvas. Then I bought these big sheets of paper, and I made these drawings of LA, but they looked . . . What did they look like?

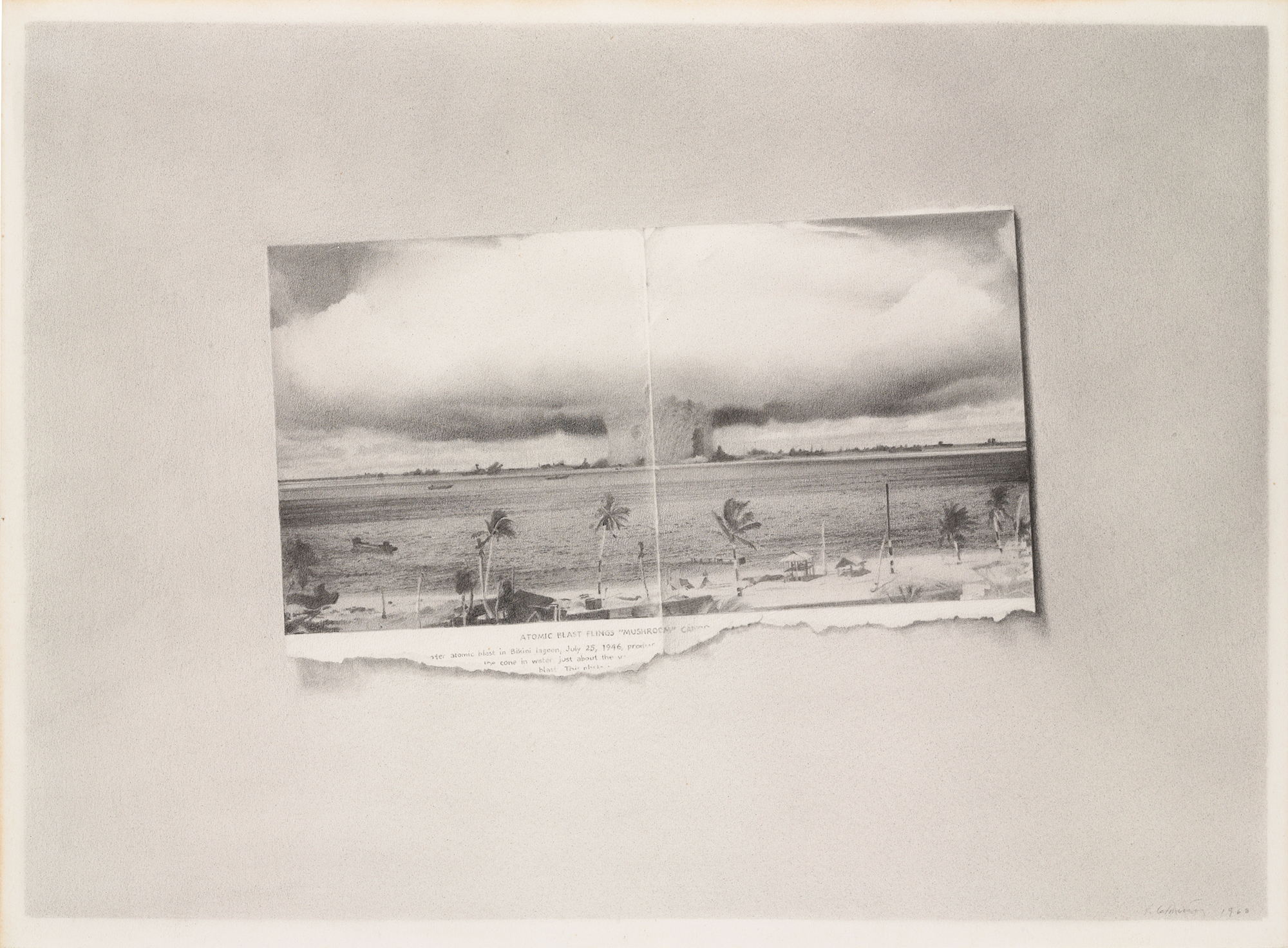

Vija Celmins, Bikini, 1968. Graphite on acrylic ground on paper

© The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Vija Celmins, Porsche, 1966–67. Oil on canvas

Learoyd: I saw a painting of yours. It was a painting looking out of the window of a car. I think it’s a Porsche driving down a highway.

Celmins: No, no. That was later. So anyway, in California, I veered away from doing totally abstract work because I didn’t think I could make it somehow strong enough. See, when you’re making a painting, it has to have some density. It’s a little more physical than just the photograph, I hate to tell you. The surface has so much art to play. Is it going to be a slick, dopey surface? Or is it going to be a thick, blobby surface? It has a visceral quality. I began to realize also that there was me that was not in the work— and I sort of started putting me in the work, my experiences. I started painting objects. Food. Everything.

Learoyd: The ham hock?

Celmins: I painted all the food I ate.

Learoyd: So, this is where the photographic thing comes in. Let me tell you . . .

Celmins: Wait. Let me tell you. I didn’t look at the photographs. But then, with Soup (1964), I had this bowl of soup. That actually came out of a little photograph from a housekeeping magazine.

Learoyd: But tonally, those paintings—the lamps, the ham hock—they have a relationship to photography because you’ve chosen not to overemphasize the color.

Celmins: I had this very gray studio, a long gray concrete studio. I was going to see what I could do with what I could see. But whatever you do is sort of whatever is inside you, I guess.

Learoyd: Things are gray. A lot of things are gray.

Celmins: Okay, so this is how I moved into sometimes using a photograph. I went looking for war books so I could understand what we went through, and there were very few war books at the time. This was in the early ’60s. I found a few things, which I tore out of books, and I painted some airplanes, because I used to love hearing the American bombers coming. ZzzzZZZZ. I went through this period where I tried to find a relationship to the work that was not so borrowed from what was out there. That’s when I fell in love with the grays, because the photographs were all gray for World War II. I got to painting the airplanes, seeing if I could make them fit like a painting, but still be like an object.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Description

Subscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Learoyd: You look at a picture on the wall, and it’s either an object or a window, I guess.

Celmins: I never see a window. It’s a flat piece of paper, and it’s got a relationship in the real world in front of you. It’s a very subtle feeling that, somehow, is dimensional or flat at the same time. Then also, you try to figure out how you’re going to paint it, whether you’re going to paint it really smooth, whether you’re going to jazz it up, how are you going to handle the thing. You’ve got to remember that paint is like cheese. It’s just totally malleable.

Learoyd: All the possible permutations of what can happen with that bit of goo.

Celmins: Basically, you can’t really say too much about it without sounding a little stupid. But you’re actually making an experience for somebody. You’re not only experiencing an image, you’re experiencing the reality of the room and the flatness. I can’t stand it when things jump out of the painting.

Learoyd: We’re sitting here. We’re looking at a drawing. Could that drawing have existed without the photograph?

Celmins: I don’t know. I guess because it’s just graphite and paper that maybe it feels more like a photograph. I don’t think I could have done that kind of precise drawing without a photograph.

Learoyd: I think that people look at your drawings and paintings and think they look photographic sometimes. And when people look at my photographs, sometimes they say they look painterly, but they couldn’t be more photographic.

Celmins: You have a barrier, which is really the paper that you print on. My work can be very soft and dimensional.

Learoyd: The enormous problem with photography is its surface.

Celmins: People now look at art as if it is photography, which is also totally wrong. You have to let yourself experience how the edges are, how the thing sits.

Learoyd: There’s a weight to your work that’s often quite small. I know you’re painting bigger now. But a lot of the things were quite small. And there seems to be this sort of density of the object. Were the star drawings done from scientific photographs?

Celmins: I began to fall in love with the lead of a pencil. I have this whole thing where I got involved in space because I liked all that stuff coming back, all those images. And I used the images, and then I found these things of the outer stars and galaxies. They are not really stars. They’re galaxies. But it’s a way of pushing the pencil to the utmost degree, the very last things.

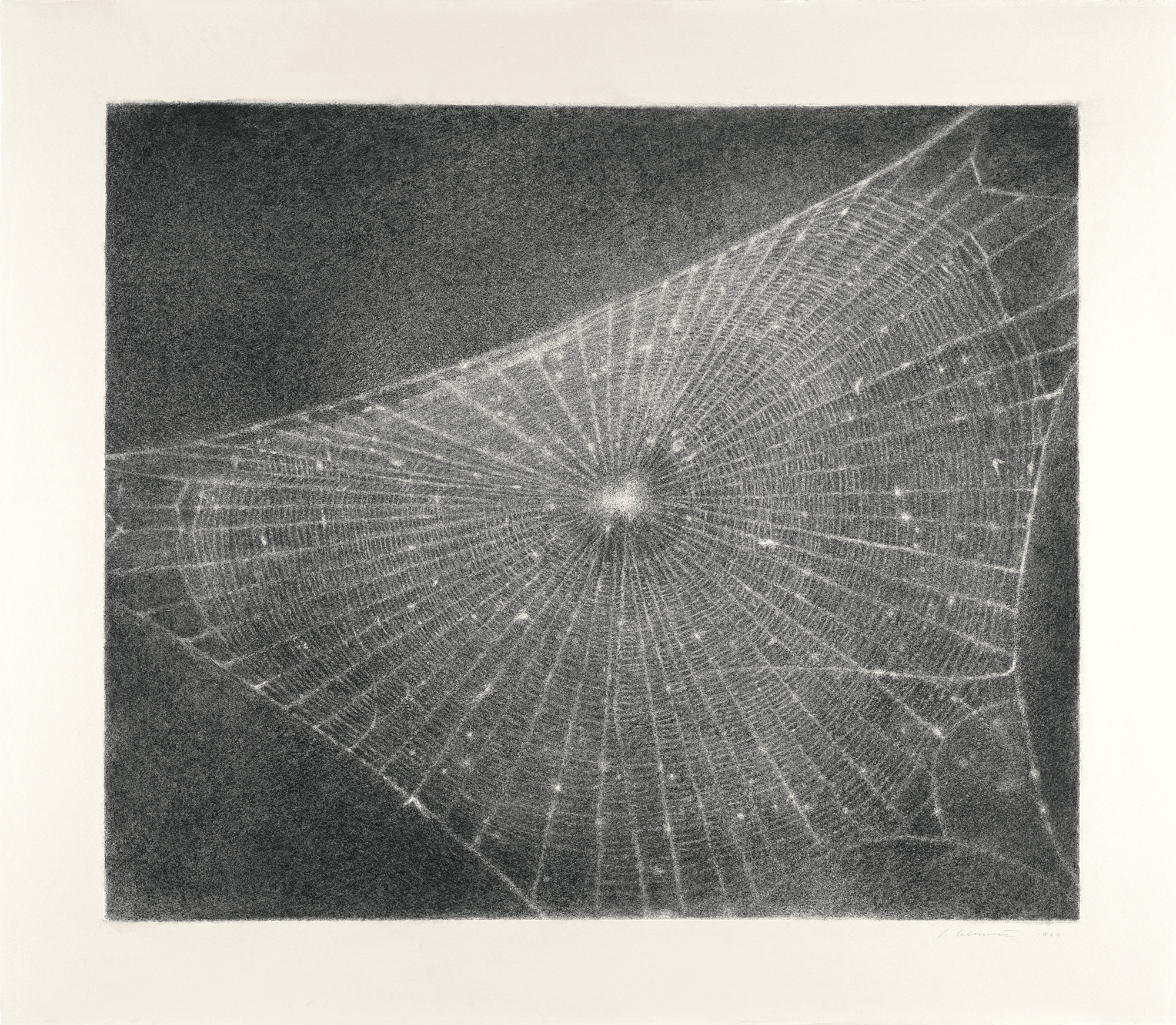

Vija Celmins, Web No. 1, 1999. Charcoal on paper

Richard Learoyd, Looking away from Lacock, 2013

© and courtesy the artist

Learoyd: And what about the spider webs?

Celmins: Oh, the spider webs? Well, I thought that I was sort of like a spider myself. I found these little books of spiders, and I thought, I’m like the spider myself, taking all the things. These were also all drawings. Then, did I do a painting of the spider web? I think I tried one. I liked the pencil.

Learoyd: Well, you can just pick it up.

Celmins: I probably liked it because I didn’t like sloshing around. And then finally, I said to myself, I have to start painting. By this time, I moved to New York, thank goodness, because the audience was more sophisticated here, and there were more museums, and there was more of a supporting group. I finally had to let go of the pencil and say, I’m going to pick up the brush, because it’s capable of doing a much more dimensional thing. When you’re looking at something, you’re actually looking at an object. You can’t run to the illusion. That’s what photography did, which was bad—you run to the image, because the image is so exquisite.

Learoyd: It’s perfect. It’s a perfect thing.

Celmins: But the experience is total. You actually made your photographs more interesting by making them so bit by bit by bit. But still, it’s not painting.

Learoyd: What photographers have to do is, they have to try to find excitement in the exterior world to make the object resonant enough to hold that illusion.

Celmins: Yeah, but you made some boring things, too, like the trees, which I love.

Learoyd: They’re very boring.

Celmins: I like the really boring thing. Yeah, that’s one thing that the photographer can do, which is very difficult to do in the painting, because somehow it kills the way that you’ve constructed the paint to act. And making the paint act in different ways is a big part of painting.

My tools are like hours, and it becomes a real part of the work. Whereas in photography, it’s instantaneous, and then you pick which image.

Learoyd: I was never interested in that side of photography, because my life isn’t very exciting. I just go home. I go to the studio.

Celmins: Well, we’re not talking about your life, we’re talking about the object you’re making.

Learoyd: The object. Exactly. But I think a lot of photographic people, they have to sort of go into the world and seek this subject.

Celmins: Yes, they get very interested in the subject matter. Your method involves that slow way of building the image and making it so precise that it hurts you to look at the thing. It’s really very shocking, in a way.

Learoyd: Yeah. But I think that my problem, going back to the idea of the surface, is that I use a paper that is incredibly shiny, because it means it has no surface. I hate photographic surfaces.

Celmins: I think people now look at all art as if it’s a photograph, which is really upsetting. And they also paint it as if it’s going to be a photograph, and it’s very graphic and sort of stays on the surface. I just saw a Francesca Woodman show, which is totally different. Really upsetting to look at the photographs, because it looks like the devil is after her.

Learoyd: It’s very raw, isn’t it? A very raw sort of expressionism.

Celmins: Right. You have a very different quality. With your work, your eyes think, Oh, my God, I can’t look at any more. It’s so incredibly precise. But hers is emotionally upsetting in a way. Like, I’m running through my short life with this instrument in my hand. See the corners of rooms and places to hide.

Learoyd: Pretty horrible. But so powerful. I didn’t get to see your show last year at Matthew Marks Gallery, but there were some quite big paintings, right?

Celmins: Yeah, I started letting, maybe, some of the paint be a little bit more. Sometimes, I sort of hide the painting, but I let it have a little bit more of an expression. You realize—finally, in my old age —that the paint has its own life, that it can be thin and fat, and it makes it very dimensional. And then sometimes, some of the work that was really small was very drawing related, but drawing with the paint.

Vija Celmins, T.V., 1964. Oil on canvas

Vija Celmins, Envelope, 1964. Oil on canvas

All works © the artist and courtesy Matthew Marks Gallery

Learoyd: If somebody sees something that relates to how they see it with their eyes, they think that’s photographic, right? So they go, “Oh, that’s a sort of photographic reference.” Because it’s an interpretation that they understand.

Celmins: I really resent that too.

Learoyd: Because the nuance of painting is the ability to do that, or not do that, but it’s a choice. Whereas in photography, there’s no choice.

Celmins: But the painting itself has a life that’s connected to the artist. The best photography has some relation to seeing something that relates more to life-experience seeing, and the way it’s made is much more hidden than in a painting, which is really made out of dust with your hands and brushes and stuff. Sometimes, I hide that, and sometimes, I show more of it.

Learoyd: I think it’s interesting that in photography now, there are more people interested in photography than ever, and yet, there’s so much terrible photography.

Celmins: Every single person is a photographer. And the subject is interesting without the experience of the room. Painting itself is more restrictive. The image is made out of other material, and it has a relation to your body, and how big it is, and how small it is, and how smooth it is, and how rough it is. It’s just got a little bit more experience.

Learoyd: The sort of success or failure as an artwork is whether it contains enigma in some way.

Celmins: Maybe enigma.

Learoyd: I think your relationship to photography is that it’s been of value to you.

Celmins: Well, sometimes there’s the image in my head, and I walk along, and I see a book that’s open in a bookstore, and there’s an image that I may have done myself. I see the grays that I’ve been looking for in the photograph, and I sometimes say, Oh, wow, I’ll follow this and see what I can do with it.

Learoyd: But the things themselves, the objects that you’re making, the paintings, they’re just very much of themselves. They have their own gravity.

Celmins: They don’t really mean the things that people think they mean.

Learoyd: One last topic that we can go into, which is about the sort of generation of a personality in artwork. The problem with photography is that everyone has the same tools. I decided I didn’t want to play with the tools that everybody else had. So, I made cameras, and I used materials in a different way. And you rejected abstract painting, asking instead, Well, what am I surrounded by?

Celmins: Abstraction actually is more complicated than that. But I don’t know what to think about the photograph. The photograph has its own life that I don’t know that much about. We have them everywhere. And for you to make such an unusual-looking experience is pretty extraordinary.

Learoyd: And you leave so much space for the person looking at your paintings and drawings. So much room for interpretation.

Celmins: But you’ve got to realize that it’s material. You see, it’s not an illusion, the painting.

Learoyd: It’s a thing.

Celmins: It’s real. There’s dust on it. It’s the pencil being pushed. It’s the material.

Learoyd: It’s not telling. It’s an invitation, isn’t it?

Celmins: Well, it’s an invitation to figure out . . . I don’t know what it is. But we’re all doing it, aren’t we? I mean, the question is how to be able to experience somebody else’s work in more than just a snap, and to be able to see aspects of it that are really unsayable and have to be in the area of experience.

Learoyd: They have to be experienced.

Celmins: They cannot be said. If you use an image, you realize that the image is an interpretation of something that is not in front of you, that is made by somebody, and how it’s made. It’s like all these instantaneous things that occur.

Learoyd: In a painting, there’re a million decisions.

Celmins: Yeah. Making a work of art, there’re a million decisions. And sometimes, the decisions are harder for people to see, and sometimes, they’re more obvious. I don’t know whether one is better than another. It’s a complicated thing that people do.

Learoyd: I know that in photography now, the way that people take photographs, they’re going to take a picture of this glass. They take fifty pictures of this glass, and then decide which is the one that they like. So, there’s no decision-making. It’s editing rather than making decisions.

Celmins: My tools are like hours, and it becomes a real part of the work. Whereas in photography, it’s instantaneous, and then you pick which image. It’s hard to do either one, it seems to me.

Learoyd: It’s all pretty difficult.

Celmins: It’s all pretty hard for you. You made your own camera and everything. I was going to . . . never mind.

Learoyd: Go on. Tell me. I want to know.

Celmins: I sometimes think that people have lost some ability to experience things in a more complicated way because life is so full of stuff now, and the imagery is everywhere. Remember how rare painting used to be? And how rare art making? Actually, it was the only thing before photography took over and there were images everywhere—but not images like you’re making.

Learoyd: Photography can be incredibly moving. You come across a picture of an old girlfriend or a lover. It’s not even sentimental or mawkish. It’s just an evocation of this other experience, and you’re taken back. And all those sensations.

Celmins: And how about seeing those early photographs of the Chinese emperors? And the Pyramids? I love to see all those early photographs. How about all the animals you get to see that you will never see?

Learoyd: That are extinct.

Celmins: You see? Painting does not work that way. And you have made your work sort of like that, but also more like art. Most photographs are not art. They’re information. But there are thousands and thousands of painters now.

Learoyd: With the advent of digital photography, I’ve taken less pictures in the last twenty years than a normal photographer will take on a fashion shoot in one day.

Celmins: Well, you’re a slow photographer.

Learoyd: Yeah.

Celmins: And you have a slow camera.

Learoyd: I have everything slow. I’m slow. The whole thing is slow.

Celmins: I like that.

This interview originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting.”