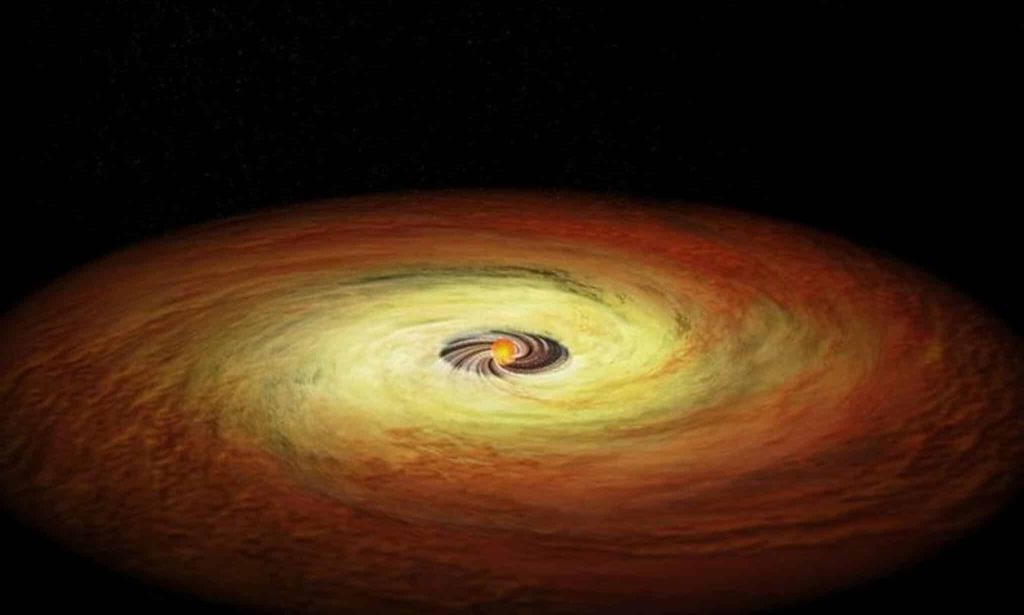

This illustration shows a lower mass star surrounded by its planet-forming disk of gas and dust. The planet formation process would cause gaps, not shown in this illustration, to appear in the disk. The streams near the center show how matter from the disk is still falling onto the star. (Credit: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss)

In a nutshell

• Astronomers have discovered a 34-million-year-old planet-forming disk around a small red star more than 30 million years after such disks typically disappear, challenging our understanding of how long planets have to form.

• The disk is extremely carbon-rich, containing 14 different molecular species including numerous hydrocarbons, with very little water vapor detected. This chemical signature suggests planets forming in such environments would likely have very different compositions than those in our solar system.

• This discovery may explain features of planetary systems around small stars like TRAPPIST-1, as the extended presence of gas allows planets to migrate into their final orbits, potentially reshaping our understanding of where habitable worlds might form.

TUCSON, Ariz. — Thirty-four million years is a long time to wait for anything. It’s longer than humans have existed as a species. In space, where things happen over billions of years, it might seem like a blink of an eye, but for a disk of gas and dust surrounding a young star, it’s practically an eternity. Astronomers have long thought these disks, where planets are born, were short-lived, disappearing after just a few million years. So when researchers pointed the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) toward a small red star in the constellation Columba, they weren’t expecting to find what looked like a cosmic fossil that should have vanished long ago.

In a new discovery published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, astronomers have spotted something they thought couldn’t exist: a 34-million-year-old disk of gas and dust still containing planet-building materials. Using the JWST, they found this cosmic pancake around a small red star with the catchy name WISE J044634.16-262756.1B (or J0446B for short). This discovery is comparable to finding a dinosaur still walking around today; these planet-forming disks typically disappear within just 10 million years.

“In a sense, protoplanetary disks provide us with baby pictures of planetary systems, including a glimpse of what our solar system may have looked like in its infancy,” says lead study author Feng Long, from the University of Arizona’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, in a statement.

A Carbon-Rich Cosmic Laboratory

This elderly disk isn’t just hanging around; it’s a buzzing chemistry lab. The Webb telescope revealed it’s packed with carbon-based molecules and hydrocarbons, essentially an organic chemistry factory that’s been operating for tens of millions of years longer than anyone thought possible.

The research team found 14 different molecular species, including familiar compounds like methane as well as more complex hydrocarbons like acetylene, benzene, and ethane. These chemicals closely match what’s seen in much younger disks, suggesting that planet-building activities might continue far longer than previously believed.

“Although we know that most disks disperse within 10 million to 20 million years, we are finding that for specific types of stars, their disks can last much longer,” adds Long. “Because materials in the disk provide the raw materials for planets, the disk’s lifespan determines how much time the system has to form planets.”

Carbon-Rich, Water-Poor

Perhaps the most striking feature of this ancient disk is what’s missing: water. The disk is extremely carbon-rich but has very little water vapor. The carbon-to-oxygen ratio is more than double what we see in our solar system, indicating that the disk has gone through a unique evolution where carbon-bearing gases have accumulated while oxygen-rich compounds like water have diminished.

J0446B orbits a small red dwarf star with only about 18% of our Sun’s mass, located 82 light-years from Earth. The star belongs to a group of stars that formed together about 34 million years ago. Despite its age, the disk still shows signs of feeding material onto the star, a process we usually only see in much younger systems.

“As long as the star has a certain mass, high-energy radiation from the young star blows the gas and dust out of the disk, and it can no longer serve as raw material to build planets,” says Long. But this clean-up process appears to work differently for very small stars.

How Did This Disk Survive So Long?

To figure out why this disk has stuck around for so long, the researchers ran computer simulations that point to something unexpected: the material in the disk moves at an exceptionally slow rate, allowing it to persist for millions of years. It’s like a slow-motion version of what happens in disks around larger stars, with extremely low viscosity. This is essentially the cosmic equivalent of molasses. This slow development would allow the disk to evolve very gradually, explaining its exceptional longevity.

“We detected gases like hydrogen and neon, which tells us that there is still primordial gas left in the disk around J0446B,” says Chengyan Xie, a doctoral student who worked on the study.

These gases show this is an original planet-forming disk, not a second-generation “debris disk” formed from collisions between already-formed asteroids or planets.

What This Means for Planets and Possibly Life

(Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

This discovery could reshape our thinking about planets around small stars. A particularly interesting example is the TRAPPIST-1 system, located 40 light-years away, which has seven Earth-sized planets orbiting a tiny red dwarf star. Three of these planets sit in the “habitable zone,” where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist.

“To make the specific arrangement of orbits we see with TRAPPIST-1, planets need to migrate inside the disk, a process that requires the presence of gas,” says study co-author Ilaria Pascucci from the University of Arizona. “The long presence of gas we find in those disks might be the reason behind TRAPPIST-1’s unique arrangement.”

If planets were to form in carbon-rich environments like J0446B, they would likely have very different compositions than those in our solar system, possibly with atmospheres rich in hydrocarbons rather than water and oxygen.

While our solar system formed around a larger star with a much shorter disk lifetime, systems like J0446B could be the norm rather than the exception across the universe. With small red dwarf stars vastly outnumbering Sun-like stars, these extended timelines for planet formation might actually represent the most common path to creating new worlds: a slow, patient process that unfolds over tens of millions of years.

Paper Summary

Methodology

The research team observed J0446B using the James Webb Space Telescope’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI). Observations were conducted in January 2024 as part of JWST’s Cycle 2 program. The team used a four-point observation pattern to subtract background noise and carefully calibrated integration times for high-quality data. They processed the raw data to remove noise patterns, subtracted the dust continuum emission to isolate molecular emission lines, and applied statistical modeling to determine the disk’s physical conditions.

Results

The JWST observations revealed 14 molecular species in the disk, including nine carbon-bearing molecules, two nitrogen-bearing molecules, two oxygen-bearing molecules, and molecular hydrogen. The team also detected ionized neon and argon—all first-time detections in a disk of this age. Water vapor was barely detected, confirming a carbon-rich environment. Hydrocarbons were found at temperatures of 250-300 Kelvin in the innermost region of the disk (0.05-0.1 astronomical units). The carbon-to-oxygen ratio was estimated at more than double the solar value.

Limitations

This study focuses on just one disk, making it unclear whether J0446B represents a common evolutionary pathway or an unusual outlier. The MIRI instrument, while powerful, still has resolution limitations that affect the detection of certain molecular lines and their spatial distribution. The statistical models used incorporate some simplifying assumptions that may not fully capture the disk’s complexity. Additionally, the estimated mass accretion rate sits at the borderline between accretion and stellar activity, creating some uncertainty about ongoing accretion.

Discussion and Takeaways

The discovery challenges the conventional timeline of disk dispersal, suggesting disks around low-mass stars can persist much longer than previously thought. This extended lifetime provides more time for planet formation, potentially explaining the abundance of rocky planets around M-dwarf stars. Computer models indicate that maintaining this carbon-rich chemistry for tens of millions of years requires extremely low viscosity, allowing material to move through the disk very slowly. The study supports a scenario where inner disk chemistry evolves through phases: initially water-rich as icy particles drift inward, then carbon-rich as water-rich material accretes onto the star and carbon-rich gas flows inward.

Funding and Disclosures

This research received support from several sources, including a NASA Hubble Fellowship grant to Dr. Feng Long. Additional funding came from the Space Telescope Science Institute, the National Science Foundation, UK Research and Innovation, the Ministry of Education of Taiwan, the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan, and the Beijing Natural Science Foundation. The researchers declared no competing interests.

Publication Information

The study, “The First JWST View of a 30-Myr-old Protoplanetary Disk Reveals a Late-stage Carbon-rich Phase,” was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on January 10, 2025 (Volume 978, L30). The research was conducted as part of the JWST Disk Infrared Spectral Chemistry Survey (JDISCS) collaboration, involving researchers from multiple international institutions.