About eight years ago at an after-party in Chelsea, I noticed another guy that sort of looked like me: a white guy with a shaved head and beard, a Brooklyn fag archetype. When we were finally face-to-face, I said, “I guess we could do a kind of Persona thing,” referring to Ingmar Bergman’s 1966 art film, though I’m not sure I spelled that out. Kevin said, “Yeah, I love that movie.” So I handed my Polaroid camera to a friend, and we set about re-creating some of the extreme twinning close-ups. The resulting pictures were nerdy, sexy, and kind of spooky, rematerializing images that lived privately in our heads, becoming a psychic scrim over us in real time.

Between my sophomore and junior years of high school, in 2004, I saw Persona projected in a classroom at a do-gooder publicly funded summer school in North Carolina—god bless. I had consumed a mainstream diet of television throughout the 1980s and 1990s, and this was the first time I ever saw a movie that I realized was an artwork. The revelation, even if I didn’t have the language for it, was the way it made me conscious of its visual form, the incandescent force of images in and of themselves.

© AB Svensk Filmindustri (1966). Photograph by Sven Nykvist

Persona was released on DVD that year, so I ordered a copy off eBay and set about trying to understand its impact on me. In an early scene, a skinny boy approaches a hazy abstract screen switching between rear-projected images of two women’s faces. He holds out his hands, rubbing them across the surface, but whatever he touches, it isn’t the women or the pictures, which evanesce and recede. These morphing scenes mirror our psychic position as viewers of the film we’re about to watch, in which two women blur into and out of each other. Playing it over and over at night—I never was chill—I started pausing the DVD and drawing every frame.

When I told all this to my hot doppelgänger, also a painter, he said he’d made Persona drawings too, studies of a famous scene: a roughly minute-long static close-up of Liv Ullmann, stone still as the screen slowly dims to darkness, at which point she finally shifts into profile, pressing her hands over her face. At first, you wonder if it’s a photograph, but the Bach chamber music keeps playing, and then the light changes unevenly, and you realize she’s making herself into a still image in real time. He envisioned drawing a long row of them, a gradient fading to black.

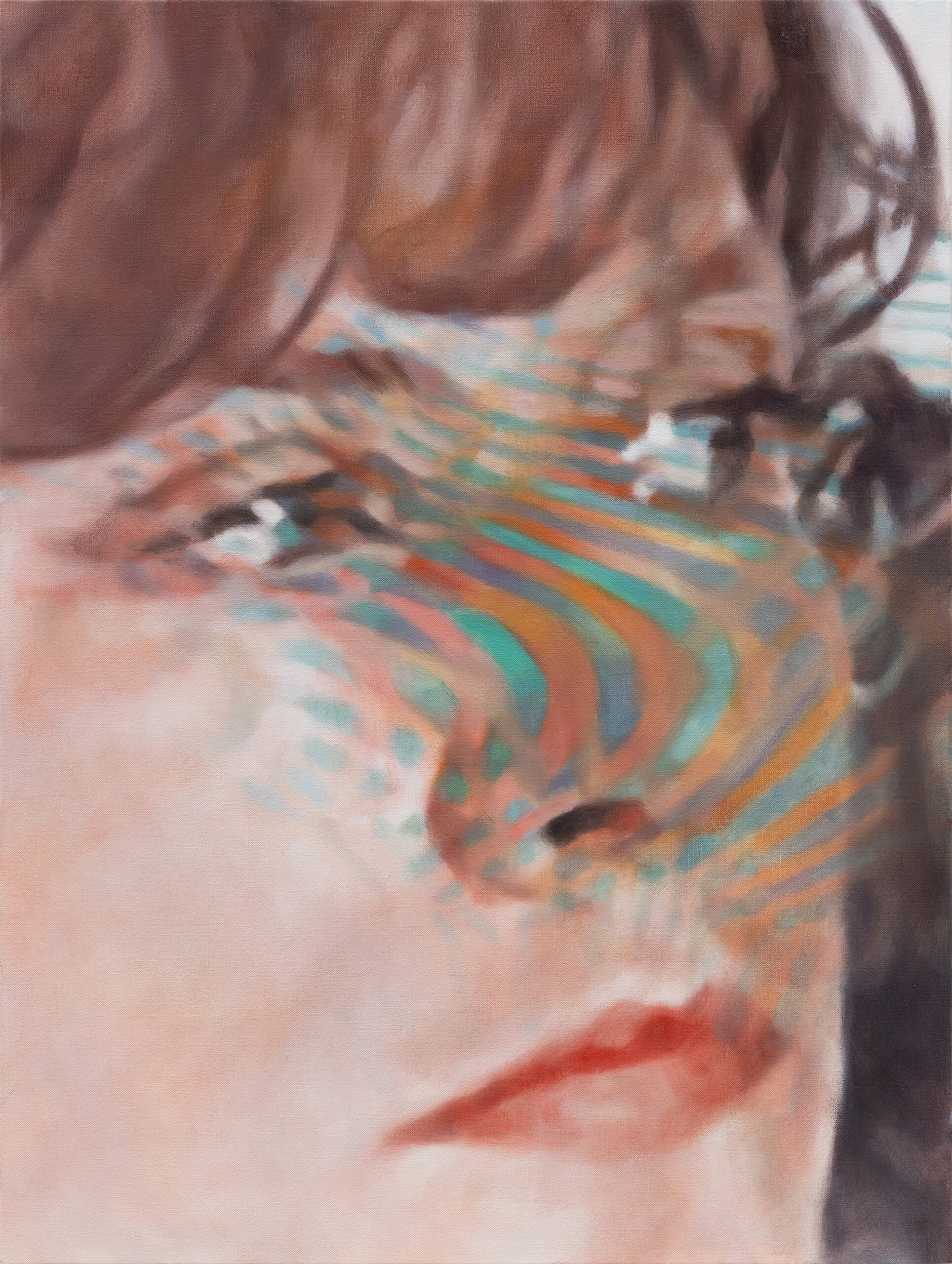

Judith Eisler, Isabelle (side eye), 2022. Oil on canvas

© and courtesy the artist

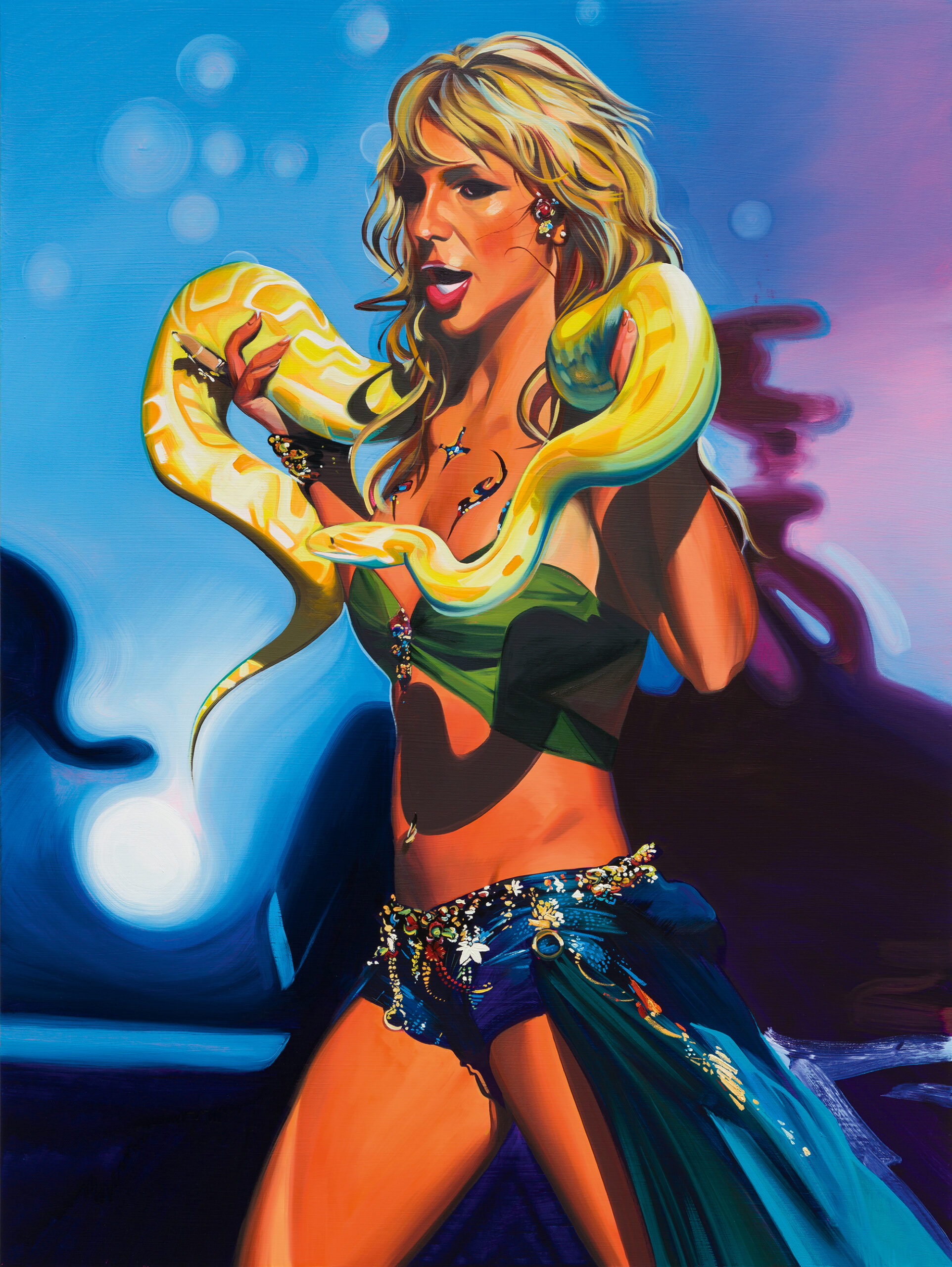

Sam McKinniss, Britney Spears, 2021. Oil on linen

Courtesy David Kordansky Gallery

I recognized a shared impulse—an intense connection with these film images, and the attempt to come to terms with their power by remaking them—while looking at Judith Eisler’s exhibition Dreams, Jokes, Mistakes at Casey Kaplan, in New York, last fall. Her canvases present an ambiguously recognizable pantheon of art-film goddesses (Isabelle Huppert, Anna Karina, Romy Schneider) as well as a mixture of pop heroines (Debbie Harry, Grace Jones, Britney Spears). Throughout the 1990s, she’d set her camera on a tripod facing a television, taking pictures from paused VHS tapes at moments of maximum psychological potency and visual uncertainty. As technology evolved, her source material eventually came to include imagery photographed from computer screens and internet screenshots, incorporating pixilation, moiré patterns, and colder tones.

Painted lush and shiny though very flat, when encountered as objects in person Eisler’s canvases are almost abstract, slowing the act of looking in ways that work against the image as it exists as either a photograph or film. Eisler, born in 1962, on the cusp between baby boomers and Gen Xers, uses an approach that is decidedly post–Pictures Generation, a small but influential photography-driven movement of the late 1970s and ’80s whose artists appropriated mass-media and art-historical images to upend notions of authenticity, and who saw the seductions of painting as suspect. The critical tide shifted in the 1990s and early 2000s with the international success of the Belgian artist Luc Tuymans, whose ghostly, aggressively spare paintings dissociate historical photographs, textbook diagrams, and film stills, mounting a sustained philosophical interrogation of the political and psychological utility of images. However, for all its similar coldness and flatness, there is a uniquely devotional aspect to Eisler’s work, verging on fandom. In her returning over and over to the same actresses, there is a sense that Eisler is charting her own personal identifications—that they are images she wants to live with for hours on end, making painting an indefinitely attenuated space of self-reflection.

Cynthia Daignault, God Bless You, 2024. Oil on linen. Installation view, Night Gallery, Los Angeles

Courtesy the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles

Eisler’s art prefigures a kind of image-driven painting, using references to film and pop culture, that has lately become ubiquitous. Take Cynthia Daignault’s God Bless You (2024), a series of twenty-four black-and-white oil paintings, each 12 by 16 inches, which collectively represent one second of projected celluloid depicting the famous shot of Ingrid Bergman at the end of Casablanca (1942). In close-up against an almost blank background, her face lit like a sculpture held in perfect stillness, staring at Humphrey Bogart off-screen, she delivers her final line: “God bless you.” Bergman does not quiver or blink, moving only her lips, almost whispering the phrase in a single breath. It’s the understated culmination of the high-drama plot, where the actress’s face processes a number of overlaid emotional switchbacks, her realization mirroring that of the audience, all looking for the last time.

In being split into twenty-four individual paintings, the single filmed second is not only extended indefinitely but expanded into a matrix. To produce an exact likeness of one of the most famous images in the world—repeatedly, so the differences can be compared—is a virtuoso feat that serves to underscore the vitality of painting as a medium today. Rendered with an almost impressionistic hand, the broad luscious strokes emphasize how the work is not the result of a photomechanical process but handmade, an act that aggregates and condenses time. This approach opens up an entirely different way of relating to images, a step back from their flow and a meditation on that astonishing affective weight.

Aperture Magazine Subscription

0.00

Get a full year of Aperture—the essential source for photography since 1952. Subscribe today and save 25% off the cover price.

In stock

Aperture Magazine Subscription

Description

Subscribe now and get the collectible print edition and the digital edition four times a year, plus unlimited access to Aperture’s online archive.

Born in 1978, at the transition between Gen Xers and millennials, Daignault represents a broader generational attitude that is now coming fully into view. While film as subject matter seems to be about another era, these artworks effect a sleight of hand because in our present moment of social media all categories of pictures are placed on an equal horizon: the simultaneous and contextless expanse of the internet. As such, the supposed anachronism of these references as well as painting itself combine into an unexpectedly agile device for addressing our present image world.

No painter embodies this change more fully than Sam McKinniss, born in 1985, who paints a seemingly arbitrary assortment of highly charged pop culture, often related to movies but spilling into music, TV, paparazzi shots, and viral celebrities, including Michelle Pfeiffer licking her spandex suit as Catwoman, Britney Spears dancing with a yellow python named Banana, and that little boy with boots and a bow tie yodeling in the Walmart, whatever his name was. These images, which have little in common, are equalized by McKinniss’s trademark performative brushwork and fevered chroma. Physically transformed, they function differently as paintings in a gallery space from their life online; when reintroduced to Instagram, they signify their role as paintings of famous pictures, so much that these recursive circuits are closer to their real content. McKinniss’s project feels diagnostic, pointing to the broader desire of the viewer to consume these images rather than to his own fandom. McKinniss invests each of his canvases with attention and seriousness that only partially redeem them from being a commentary on the vulgar tastes of contemporary audiences.

Courtesy the artist

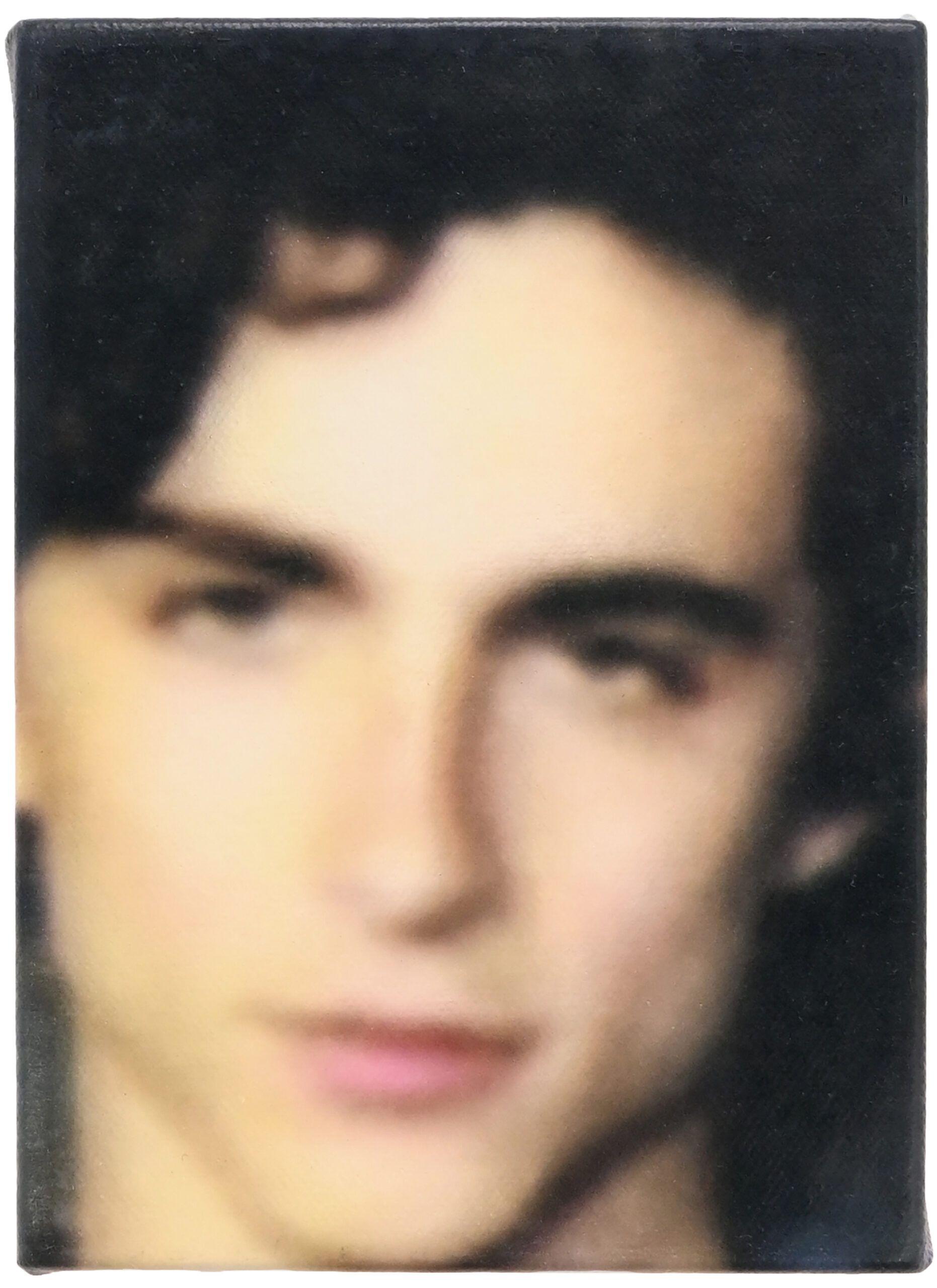

Lucien Smith’s exhibition People Are Strange, held at Will Shott gallery last autumn, offers a counterpoint. Born in 1989, Smith was a star right out of art school, surfing the spectacular market boom-and-bust of process-based abstraction famously dubbed “zombie formalism.” For his first New York exhibition in a decade, he presented grids of eighty small portraits of celebrities, closely cropped faces pulled from pictures online. The canvases are around the size of an iPhone and painted in airbrush by a robot. The results have the kind of submerged softness that recalls photographs transferred onto the tops of frosted cakes. These are clearly not made by a human hand, which intensifies their aura of degraded fetishism.

On close inspection, the images seem to dissolve in a way that mirrors the digital photograph on a screen, but held in suspension. It’s hard to shake a feeling of aggression toward the art world, with its own predatory system of publicity, and the show astutely identifies the current version of collector bait as being not decorative allover abstract paintings but figurative paintings of images culled from the internet. From the mosaic of seemingly generic celebrity, we are asked to choose our favorite. Nested within that invitation is the question, What does it say about me that I want this shitty little icon of Lana Del Rey? Or Billie Eilish? Or Timothée Chalamet? What is at stake in this fantasy of identification, commodification, and cultural consumption?

Lady Diana on board the Jonikal, 1997

API/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Witt Fetter, Diana, 2022. Oil on canvas

Courtesy the artist and Derosia, New York

These are dynamics taken up with perverse intelligence in the large paintings by Witt Fetter, an artist born in 1994. A 72-by-48-inch example titled Diana (2022), and its pendant, Jonikal (2023), shows a golden figure balancing on the end of a passerelle over a blue sea, instantly evoking the famous telephoto snaps of Princess Diana on Mohamed al-Fayed’s yacht in 1997, photographs that became emblematic of her hounded isolation and inability to escape the public’s insatiable desire for her, culminating in her tragic death the following month.

The artist was three years old when the paparazzo took this snap, which continues to live in the cultural unconscious (resurfacing most recently through its dramatization in The Crown). The recognition is immediate, cemented by the titles, so much so that it takes a moment to realize that it is not Diana we see. This blond has hair trailing to mid-back and is bare breasted, wearing only a bikini bottom. Realizing that it is, in fact, a self-portrait illustrates the strange substitutions and exchanges that characterize our attempts to see ourselves in and out of pictures today. Images are the chimeric surface of our psychic lives.

Around the same time I was drawing Persona as a gay teen in my bedroom, Britney Spears started rebelling against her good-girl image, partying with the socialite Paris Hilton and the actress Lindsay Lohan. They were terrorized by paparazzi, and pictures of them crushed into the front seat of a McLaren sports car appeared in 2006 on the front page of the New York Post with the headline “Bimbo Summit,” a title that stuck. In Fetter’s 2024 painting titled Bimbo Summit, she repeats the image, only this time it is painted as though folded, printed on a screen, and laid at an angle inside the windshield of a car. The painted car doubles the car they’re photographed inside and acts as both a cage and a means of escape. The picture is treated as a literal shield blocking another view, a site of displacement, something to hide behind, but also something we might shape and change for our own purposes.

The summit’s trio have all undergone their separate cycles of scorn and redemption and, indeed, are still present in the pop-cultural landscape, looking very much the same, almost two decades later. Following suit, our collective attitude toward this image has changed from the ridiculing of seemingly wayward young women to an acknowledgment of its being a symbol of the impossible and contradictory demands our culture makes on stars. One imagines how this photograph functioned as a complex site of self when Fetter was a young trans girl, twelve years old at the time, in which a certain kind of aspirational womanhood was inseparable from spectacular visuality, a knot of punishment and possibility. By using painting to explore these images within her synthetic scenarios, Fetter allows them to be highly conflicted, ambivalent, edged, offering a tantalizing glimpse of the future of painting as a conceptual tool of reconciliation and transformation.

This article originally appeared in Aperture No. 258, “Photography & Painting.”