Climate and science reporter

Data journalist

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe world’s largest iceberg has run aground in shallow waters off the remote British island of South Georgia, home to millions of penguins and seals.

The iceberg, which is about twice the size of Greater London, appears to be stuck and should start breaking up on the island’s south-west shores.

Fisherman fear they will be forced to battle with vast chunks of ice, and it could affect some macaroni penguins feeding in the area.

But scientists in Antarctica say that huge amounts of nutrients are locked inside the ice, and that as it melts, it could create an explosion of life in the ocean.

“It’s like dropping a nutrient bomb into the middle of an empty desert,” says Prof Nadine Johnston from British Antarctic Survey.

Ecologist Mark Belchier who advises the South Georgia government said: “If it breaks up, the resulting icebergs are likely to present a hazard to vessels as they move in the local currents and could restrict vessels’ access to local fishing grounds.”

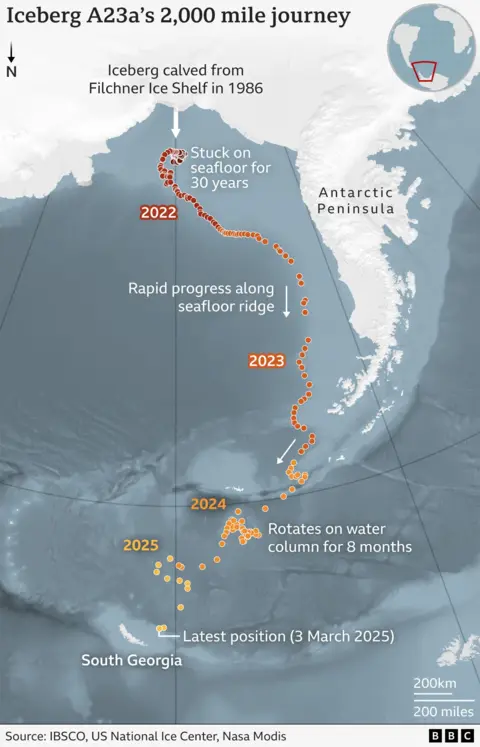

The stranding is the latest twist in an almost 40-year story that began when the mega chunk of ice broke off the Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf in 1986.

We have tracked its route on satellite pictures since December when it finally broke free after being trapped in an ocean vortex.

As it moved north through warmer waters nicknamed iceberg alley, it remained remarkably intact. For a few days, it even appeared to spin on the spot, before speeding up in mid-February travelling at about 20 miles (30km) a day.

“The future of all icebergs is that they will die. It’s very surprising to see that A23a has lasted this long and only lost about a quarter of its area,” said Prof Huw Griffiths, speaking to BBC News from the Sir David Attenborough polar research ship currently in Antarctica.

On Saturday the 300m tall ice colossus struck the shallow continental shelf about 50 miles (80km) from land and now appears to be firmly lodged.

“It’s probably going to stay more or less where it is, until chunks break off,” says Prof Andrew Meijers from British Antarctic Survey.

It is showing advancing signs of decay. Once 3,900 sq km (1,500 sq miles) in size, it has been steadily shrinking, shedding huge amounts of water as it moves into warmer seas. It is now an estimated 3,234 sq km.

“Instead of a big, sheer pristine box of ice, you can see caverns under the edges,” Prof Meijers says.

Tides will now be lifting it up and down, and where it is touching the continental shelf, it will grind backwards and forwards, eroding the rock and ice.

“If the ice underneath is rotten – eroded by salt – it’ll crumble away under stress and maybe drift somewhere more shallow,” says Prof Meijers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut where the ice is touching the shelf, there are thousands of tiny creatures like coral, sea slugs and sponge.

“Their entire universe is being bulldozed by a massive slab of ice scraping along the sea floor,” says Prof Griffiths.

That is catastrophic in the short-term for these species, but he says that it is a natural part of the life cycle in the region.

“Where it is destroying something in one place, it’s providing nutrients and food in other places,” he adds.

There had been fears for the islands’ larger creatures. In 2004 an iceberg in a different area called the Ross Sea affected the breeding success of penguins, leading to a spike in deaths.

But experts now think that most of South Georgia’s birds and animals will escape that fate.

Some Macaroni penguins that forage on the shelf where the iceberg is stuck could be affected, says Peter Fretwell at the British Antarctic Survey.

The iceberg melts freshwater into salt water, reducing the amount of food including krill (a small crustacean) that penguins eat.

The birds could move to other feeding grounds, he explains, but that would put them in competition with other creatures.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe ice could block harbours or disrupt sailing when the fishing season starts in April.

“We will have to do battle with A23a for sure,” says Andrew Newman from Argos Froyanes.

But scientists working in Antarctica currently are also discovering the incredible contributions that icebergs make to ocean life.

Prof Griffiths and Prof Johnston are working on the Sir David Attenborough ship collecting evidence of what their team believe is a huge flow of nutrients from ice in Antarctica across Earth.

Particles and nutrients from around the world get trapped into the ice, which is then slowly released into the ocean, the scientists explain.

“Without ice, we wouldn’t have these ecosystems. They are some of the most productive in the world, and support huge numbers of species and individual animals, and feed the biggest animals in the world like the blue whale,” says Prof Griffiths.

A sign that this nutrient release has started around A23a will be when vast phytoplankton blooms blossom around the iceberg. It would look like a vast green halo around the ice, visible from satellite pictures over the next weeks and months.

The life cycle of icebergs is a natural process, but climate change is expected to create more icebergs as Antarctica warms and becomes more unstable.

More could break away from the continent’s vast ice sheets and melt at quicker rates, disrupting patterns of wildlife and fishing in the region.