The beginning

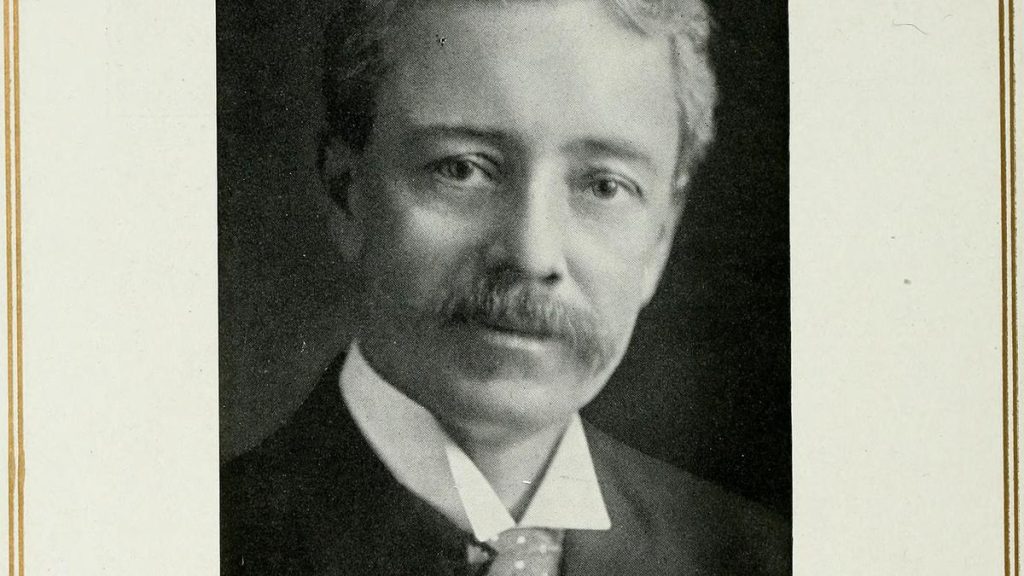

Born in Greensboro, U.S., in July 1859, Henry Louis Smith did his schooling at the local high school, which was run by his uncle. He entered Davidson College in 1877, and while he graduated with honours in 1881, his involvement with them lasted much longer.

He served as the principal of the Selma Academy for five years, during which time he not only demonstrated his teaching ability, but also how he could engage in promotional activities. During his tenure, the school’s enrollment quadrupled, and a new building was constructed for classes.

That brought him back to Davidson College, where he was recruited to be the professor of natural science (physics and astronomy). Smith, however, availed a year’s absence and put that time to good use by obtaining an M.A. degree in 1887 from the University of Virginia. He commenced his teaching after that, briefly returning to Virginia again in the academic year of 1889-90 to earn his Ph.D. in physics.

Bringing X-rays to the U.S.

On two major occasions, Smith’s scientific knowledge had positive consequences globally. The first of those was in January 1896 when he played a telling role in bringing X-rays to the U.S.

Having read about Roentgen’s recent discovery of X-rays and his experiments in Germany, Smith decided to put it to the test in his laboratory. Working with some of his students, Smith constructed an X-ray machine using Crookes tube.

While the accounts vary here as to whether or not Smith was directly involved, we can say with certainty that on January 12, 1896, X-ray pictures were produced for the first time in the U.S. A variety of objects were X-rayed, including rifle cartridges, rings and pins inside a pillbox, and even a human finger (story goes that three students bribed a janitor to let them into the anatomy lab on campus, before using a pocket knife to slice a finger from a corpse… doing all of this in secrecy, afraid of the consequences if they were to be found out!).

Smith conducted further experiments in February. He himself obtained the hand of a corpse from a local physician, and shot a bullet into that hand. The resulting X-ray image was probably the first demonstration of X-rays ability to tellingly reveal both natural and foreign objects within the human body. This picture was published on February 27 in the Charlotte Observer.

In the years that followed, Smith conducted one of the first clinical applications of X-rays. Along with a team of medical practitioners, Smith employed X-rays to detect a tailor’s thimble that a child from Harrisburg had swallowed, which the doctors then successfully removed.

Balloons for peace

The year he brought X-rays to the U.S. was also the year in which Smith grew further at Davidson College, as he was named vice-president in 1896. The turn of the century worked wonders for him as he was elected president of Davidson College in 1901.

He held that position for over a decade, departing only to become the president of Virginia’s Washington and Lee University. The fact that his father had graduated from here had been a tug strong enough for Smith to make the move and make his presence felt there.

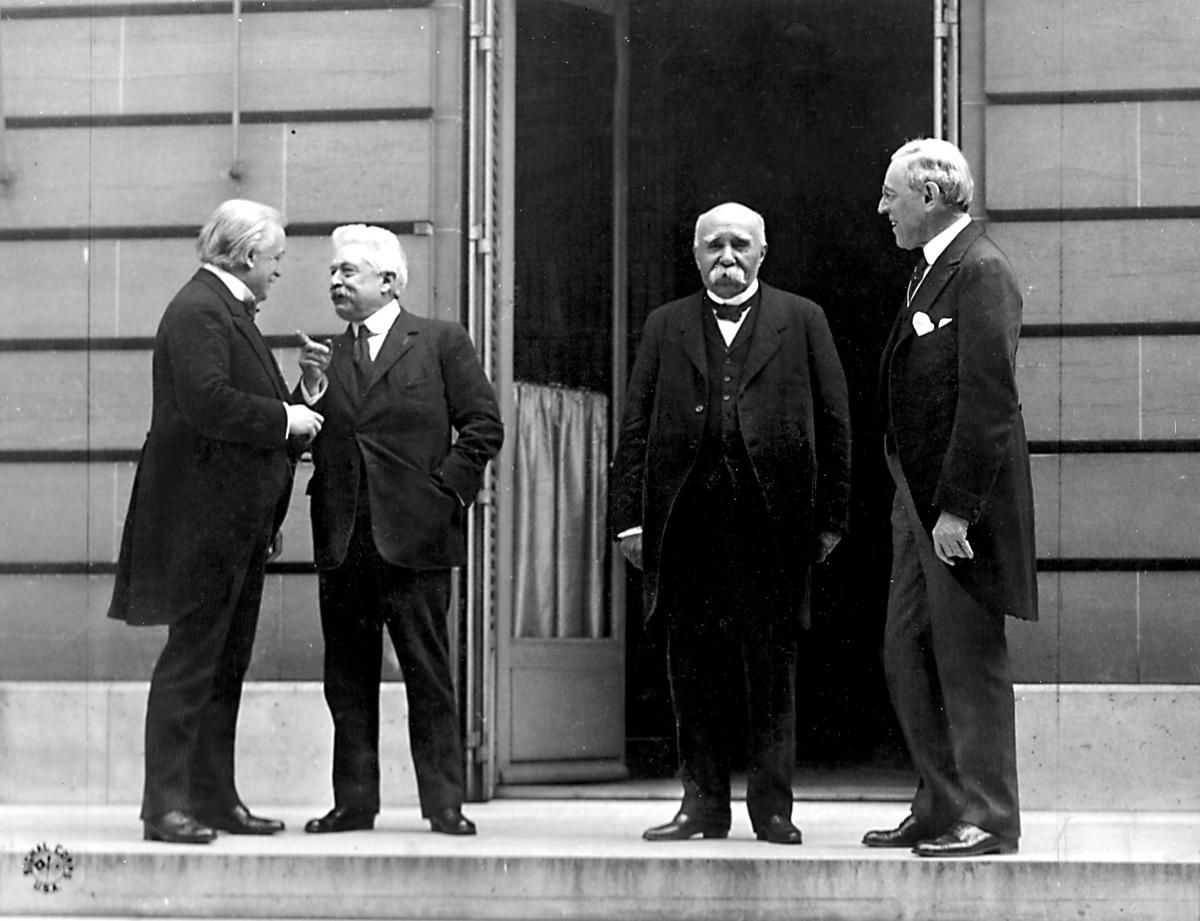

Council of Four at the WWI Paris peace conference in 1919. From left to right, U.K. Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Italy’s Premier Vittorio Orlando, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

Alas, World War I was just around the corner and it drew the energies of almost everyone involved. While it is well established that wars and the accompanying arms race usually bring benefits to the fields of science and technology, Smith ensured that science and tech provided an impetus on the peace efforts of World War I too.

Close to the end of that war, a prize was offered for those who could come up with a method of informing the German people about U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s plans for peace. Keeping in mind the prevailing winds, Smith suggested attaching Wilson’s message to gas-filled balloons and releasing them from France.

With the timing seemingly right, the Allies acted on the idea and sent across innumerable such balloons in the hope that it would be carried to Germany. The plan worked as the majority of German soldiers who surrendered carried this message with them. Wilson, in fact, credited Smith for shortening the war considerably.

Able teacher and administrator

The success that Smith enjoyed at Selma Academy was something that he was able to replicate wherever he went. Blessed with an energetic mind and endless energy, Smith more than tripled Davidson College’s enrollment during his time there, and more than doubled the size of the student body at Washington and Lee University.

An administrator par excellence, he is celebrated largely for the work that he put in to not only enhance intellectual standards, but also raising the bar for admission requirements. A gifted speaker, Smith lost no opportunity to seek funds from all sources, even if it meant travelling excessively for the cause of promoting his institution.

At heart, however, Smith was a teacher. He was recalled by students as “brilliant” and “enthusiastic” and he initiated and implemented so many projects for his students that they aptly gave him the nickname “Project”.

Even after retiring from academic life at the age of 70 in 1929, Smith remained active until shortly before his death in February 1951. As someone who set up facilities for recreation and exercises for his students as he believed that a strong body was necessary for a strong mind, Smith made sure he was agile throughout, both intellectually and physically.

***

The discovery of X-rays

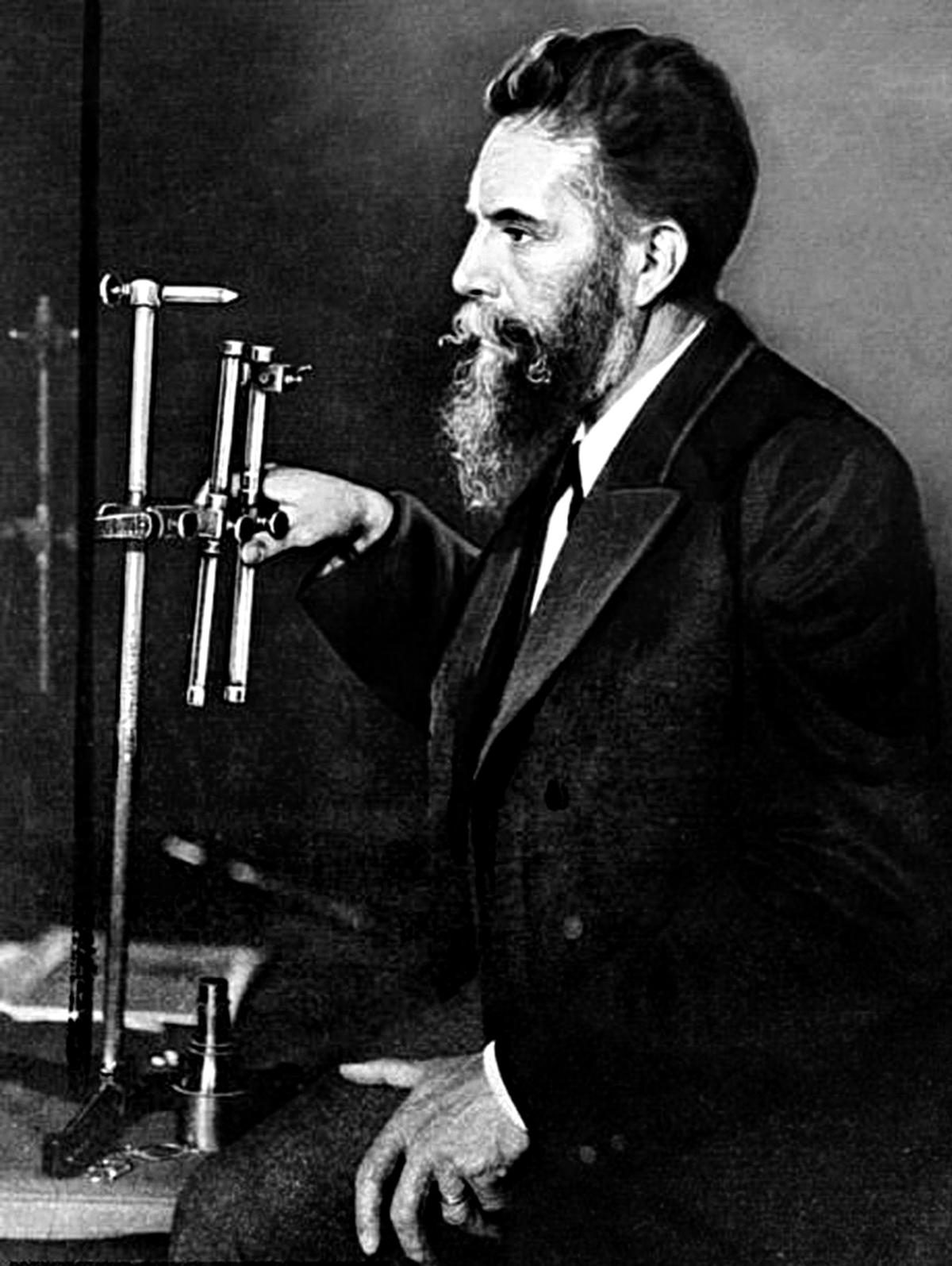

Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen

| Photo Credit:

Wikimedia Commons

A serendipitous accident was behind the discovery of X-rays by German physician Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen on November 8, 1895.

Roentgen was using Crookes tube to conduct experiments in his laboratory. This experiment involved evacuating a glass bulb and filling it with a special gas. When a high-voltage current was then passed through it, it produced a fluorescent glow.

Roentgen noticed a green coloured fluorescent light could be seen coming from a screen setting that was about 10 feet from the tube, despite the fact that the tube was heavily shielded with a black cardboard.

Roentgen came to the correct conclusion that he was dealing with a new kind of ray. He named it X-ray, going with the nomenclature used in mathematics to indicate an unknown quantity. The name stuck.

Roentgen made an X-ray image of his wife Bertha’s hand to confirm his discovery. The iconic image, which proved beyond doubt the existence of X-rays, plainly showed the bones of her hand along with the ring on one of her fingers.

Published – January 12, 2025 12:51 am IST